Biotechnology and Security: Are We Prepared?

Abstract: Biotechnology is rapidly diffusing globally. Efficient methods for reading, writing, and editing genetic information, producing genetic diversity, and selecting for traits are becoming widely available. New communities of practice are gaining the power to act on timescales and geographies that fall outside current systems of oversight. Governments and scientific communities alike are struggling to respond appropriately.

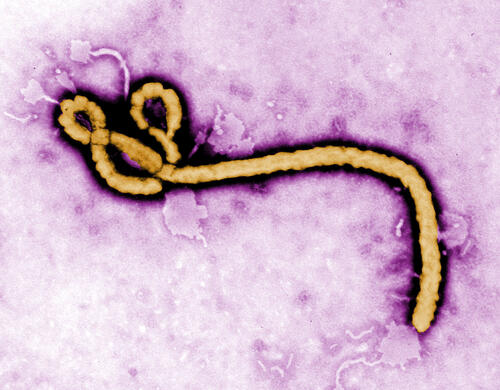

Recent controversies have brought these issues to light: “gain-of-function” research may risk causing the very pandemics it aims to help mitigate; the development of “gene drives” may drastically alter ecosystems; and crowd-funded “CRISPR kits” are giving decentralized communities access to powerful new tools. Meanwhile, a series of accidents at the nation’s premier biological labs, and recent struggles in responses to Ebola and Zika are raising concerns about the capacity to respond to biological threats regardless of their cause – accidental, deliberate or naturally occurring. The lack of mechanisms to assess the benefits and risks of advances in biotechnology has prompted reactive and blunt policy solutions including scientific and government-lead research moratoriums.

This presentation will review recent developments and discuss improved strategies for preparing for emerging biological risks. It will highlight key needs and opportunities in leadership, oversight and learning to mature our institutions to tackle long-term governance challenges.

About the Speaker: Dr. Megan J. Palmer is a Senior Research Scholar and William J. Perry Fellow in International Security at the Center for International Security and Cooperation (CISAC) at Stanford University. She leads a research program focused on risk governance in biotechnology and other emerging technologies. Dr. Palmer is also an investigator of the multi-university Synthetic Biology Engineering Research Center (Synberc), where for the last 5 years she served as Deputy Director of its policy-related research program, and led projects in safety and security, property rights, and community organization and governance. She was previously a research scientist at the California Center for Quantitative Bioscience at UC Berkeley, and an affiliate of Lawrence Berkeley National Labs.

Dr. Palmer has created and led many programs aimed at developing and promoting best practices and policies for the responsible development of biotechnology. She founded and serves as Executive Director of the Synthetic Biology Leadership Excellence Accelerator Program (LEAP), an international fellowship program in responsible biotechnology leadership. She also leads programs in safety and responsible innovation for the international Genetically Engineered Machine (iGEM) competition. Dr. Palmer advises a diversity of organizations on their approach to policy issues in biotechnology, including serving on the board of the synthetic biology program of the Joint Genomics Institute (JGI)

Dr. Palmer holds a Ph.D. in Biological Engineering from MIT, and was a postdoctoral scholar in the Bioengineering Department at Stanford University, when she first became a CISAC affiliate. She received a B.Sc.E. in Engineering Chemistry from Queen’s University, Canada.

Megan Palmer

616 Jane Stanford Way

Suite C238

Stanford, CA 94305-6165

Dr. Megan J. Palmer is the Executive Director of Bio Policy & Leadership Initiatives at Stanford University (Bio-polis). In this role, Dr. Palmer leads integrated research, teaching and engagement programs to explore how biological science and engineering is shaping our societies, and to guide innovation to serve public interests. Based in the Department of Bioengineering, she works closely both with groups across the university and with stakeholders in academia, government, industry and civil society around the world.

In addition to fostering broader efforts, Dr. Palmer leads a focus area in biosecurity in partnership with the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies (FSI) at Stanford. Projects in this area examine how security is conceived and managed as biotechnology becomes increasingly accessible. Her current projects include assessing strategies for governing dual use research, analyzing the diffusion of safety and security norms and practices, and understanding the security implications of alternative technology design decisions.

Dr. Palmer has created and led many programs aimed at developing and promoting best practices and policies for the responsible development of bioengineering. For the last ten years she has led programs in safety, security and social responsibility for the international Genetically Engineered Machine (iGEM) competition, which last year involved over 6000 students in 353 teams from 48 countries. She also founded and serves as Executive Director of the Synthetic Biology Leadership Excellence Accelerator Program (LEAP), an international fellowship program in biotechnology leadership. She advises and works with many other organizations on their strategies for the responsible development of bioengineering, including serving on the board of directors of Revive & Restore, a nonprofit organization advancing biotechnologies for conservation.

Previously, Megan was a Senior Research Scholar and William J. Perry Fellow in International Security at the Center for International Security and Cooperation (CISAC), part of FSI, where she is now an affiliated researcher. She also spent five years as Deputy Director of Policy and Practices for the multi-university NSF Synthetic Biology Engineering Research Center (Synberc). She has previously held positions as a project scientist at the California Center for Quantitative Bioscience at the University of California Berkeley (where she was an affiliate of Lawrence Berkeley National Labs), and a postdoctoral scholar in the Bioengineering Department at Stanford University. Dr. Palmer received her Ph.D. in Biological Engineering from M.I.T. and a B.Sc.E. in Engineering Chemistry from Queen’s University, Canada.