Go Bold or Go Home: The Nuclear Posture Review Must Give Biden Real Options

Editor’s note: In late September, the National Interest organized a symposium on nuclear policy, nonproliferation, and arms control under the Biden administration. A variety of scholars were asked the following question: “Should Joe Biden seize the opportunity of his administration’s Nuclear Posture Review to redefine the role of nuclear weapons in U.S. security planning? How should U.S. policy change to address the proliferation threats that the United States is facing?” The following article is one of their responses:

President Joe Biden should use the opportunity of the Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) to reduce the role of nuclear weapons in the United States’ security policy and support a forward-looking arms control approach while maintaining a safe, secure, and effective nuclear deterrent. He will have to make his views known if he wants the process to produce bold options for his consideration.

First, the NPR is the ideal place to consider the planned strategic modernization program. The Congressional Budget Office estimates the program’s cost over the next ten years at $634 billion. Maintaining a safe, secure, and effective deterrent requires that certain programs proceed, including command and control updates, the Columbia-class ballistic missile submarine, the B-21 bomber, and the B61-12 bomb. However, some programs should be reconsidered. For example, while the United States should maintain a triad that includes an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) leg, the NPR should assess whether it is necessary to deploy four hundred ICBMs. It should also take an unbiased look at whether some portion of the Minuteman III force could be life-extended, allowing the Defense Department to push out to the future the question of building an expensive new ICBM.

Pursuing all of these strategic programs would entail significant opportunity costs as less money would be available for conventional forces such as Virginia-class attack submarines, conventionally-armed missiles, and fighter aircraft. That matters. The most likely path to a nuclear exchange between the United States and Russia or the United States and China is a conventional conflict that escalates into a nuclear conflict. American conventional military power that can deter conventional conflict with peer competitors in the first place will also greatly reduce the likelihood of nuclear conflict.

Second, the NPR will provide the basis for Washington’s approach in possible negotiations with Russia regarding further reductions and limitations on nuclear arms. American officials have said that the Biden administration would seek a limit covering all American and Russian nuclear arms. The NPR should set a level for American negotiators. How about 2,500 total nuclear warheads, with a sub-limit of 1,000 deployed strategic warheads? That would require significant cuts by the United States and Russia but would still leave both with many more nuclear weapons than any other country. Such a reduction would position Washington and Moscow to effectively press China to moderate its nuclear plans.

Moscow will likely not agree to any nuclear reduction, let alone a limit of 2,500, unless Washington addresses issues such as missile defense. With this in mind, decisions in the NPR should account for decisions regarding other non-nuclear weapon programs, and vice versa.

Third, Biden has endorsed moving to a declaratory policy in which the sole purpose of the United States’ nuclear weapons would be to deter a nuclear attack on the United States or an ally or partner and, if necessary, retaliate for such an attack. Both Washington and Moscow now appear to believe the other is lowering the threshold for nuclear use. That should leave no one comfortable. Adopting a sole-purpose policy would signal a different approach from the United States.

Critics of a sole-purpose policy argue that the ambiguity in America’s current declaratory policy means that the implicit threat of the first use of nuclear weapons can help deter a conventional attack. That is a serious point, but it is almost impossible to conceive of circumstances in which an American president would authorize first use, particularly against a nuclear-armed adversary that could strike back with its own nuclear arms. Moreover, given the effort that China and Russia are devoting to developing their conventional forces, Beijing and Moscow certainly seem to believe in the possibility of great power conventional conflict, regardless of the United States’ nuclear deterrent.

The adoption of a sole-purpose policy will require consultation with allies who depend on the United States’ extended nuclear deterrent. Those consultations may prove difficult, but there are offsets (for example, American boots on the ground) that could replace a dubious threat of first use.

Right-sizing the United States’ nuclear forces (in part to free up funds for conventional forces), shaping a proposal for significant reductions with Russia, and adopting a sole purpose policy offer outcomes that a forward-looking NPR could advance. The review should offer these as options for the president’s consideration. He can then decide how bold he wishes to be.

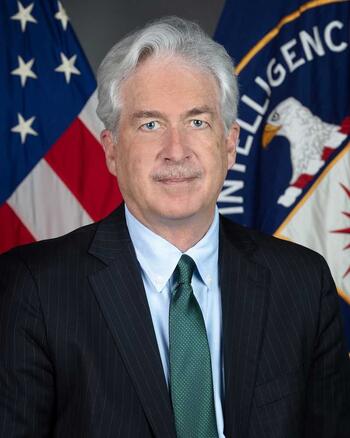

Steven Pifer is a William J. Perry Fellow at Stanford’s Center for International Security and Cooperation.

Originally for The National Interest

The NPR must position President Biden to right-size America's nuclear forces and pursue arms control negotiations.