CISAC scholars urge continued US-Russia collaboration

The United States and Russia should keep working together to stop the spread of nuclear weapons even while disagreeing on issues like Ukraine, Stanford scholars say.

In a recent article in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Professor Siegfried Hecker and researcher Peter Davis advocate continued U.S.-Russia collaboration on nuclear weapon safety and security.

"The Ukraine crisis has exacerbated what had already become a strained nuclear relationship," Hecker said in an interview. "As one of our Russian colleagues told us, nuclear issues are global and accidents or mishaps in one region can affect the entire world."

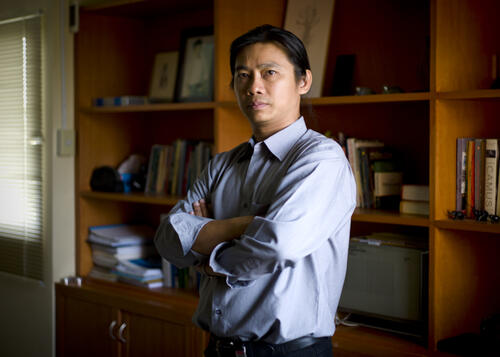

Hecker is a professor in the Department of Management Science and Engineering and a senior fellow at CISAC and the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies. Over the past 20-plus years, he has worked with Russian scientists to help stop nuclear proliferation. He and Davis returned from a trip this spring to Russia, where they met with nuclear scientists.

"We agreed that we have made a lot of progress working together over the past 20-plus years, but that we are not done," they wrote in the journal essay.

Hecker and Davis described Moscow as a reluctant partner in talks on nuclear proliferation. As for the United States, it actually backed away from cooperation first. A House of Representatives committee recently approved legislation that would put nuclear security cooperation with Russia on hold. And though the White House has opposed this, the Energy Department has issued its own restrictions on scientific interchanges as part of the U.S. sanctions regime against Russia.

But, Hecker said, "Cooperation is needed to deal with some of the lingering nuclear safety and security issues in Russia and the rest of the world, with the threats of nuclear smuggling and nuclear terrorism, and to limit the spread of nuclear weapons."

Washington does not have to choose between the two. It still can pressure Moscow on Ukraine while cooperating on nuclear issues, Hecker and Davis wrote.

They called for further nuclear arms reductions between the two countries, rather than a resumption of the nuclear arms race that took place in the mid-20th century.

Changing relationship

Hecker and Davis acknowledged that the U.S.-Russian relationship overall is changing.

"We realize … that the nature of nuclear cooperation must change to reflect Russia's economic recovery and its political evolution over the past two decades," they wrote.

For example, due to the strained relationship, nuclear proliferation programs must change from U.S.-directed activities to more jointly sponsored collaborations that serve both countries' interests.

As they noted, one huge problem is that Russia still has no inventory or record of all the nuclear materials the Soviet Union produced – or where those materials might be today.

"Moreover, it has shown no interest in trying to discover just how much material is unaccounted for. Our Russian colleagues voice concern that progress on nuclear security in their country will not be sustained once American cooperation is terminated," Hecker and Davis said.

Iran is a flashpoint

America needs Russia to help in its effort to stop Iran from building a nuclear weapon, Hecker and Davis wrote. Russia is a close ally of Iran: "Much progress has been made toward a negotiated settlement of Iran's nuclear program since President Hassan Rouhani was elected in June, 2013. However, little would have been possible without U.S.-Russia cooperation."

In a June 2 interview in the Tehran Times, Hecker said that the only way forward for Iran's nuclear program is transparency and international cooperation. He suggested that the country follow the South Korean model of peaceful nuclear power.

"In my opinion, South Korea will not move in a direction of developing a nuclear weapon option because it simply has too much to lose commercially. That is the place I would like to see Tehran. In other words, it decides that a nuclear program that benefits its people does not include a nuclear weapons option," he told the interviewer.

Hecker said that it is not in Russia's interest to have nuclear weapons in Iran so close to its border.

"Washington, in turn, needs Moscow, especially if it is to develop more effective measures to prevent proliferation as Russia and other nuclear vendors support nuclear power expansion around the globe," Hecker said.

In February, the Iranian government republished an article by Hecker and Abbas Milani, the director of Iranian Studies at Stanford University. The story ran in Farsi on at least one official website, possibly indicating a genuine internal debate in Tehran on the nuclear subject. Hecker and Milani described such a "peaceful path" in another essay on Iranian nuclear power.

Hecker is working with Russian colleagues to write a book about how Russian and American nuclear scientists joined forces at the end of the Cold War to stymie nuclear risks in Russia.

Media Contact

Siegfried Hecker, Freeman Spogli Institute: (650) 725-6468, shecker@stanford.edu

Clifton B. Parker, Stanford News Service: (650) 725-0224, cbparker@stanford.edu

Students were given two images that showed Iran's Arak nuclear facility on two different dates.

Students were given two images that showed Iran's Arak nuclear facility on two different dates.

Stanford Law School Professor Allen Weiner plays the UN Secretary-General.

Stanford Law School Professor Allen Weiner plays the UN Secretary-General.