A New Look at Cinema in Southeast Asia from Former LKC Fellow Gerald Sim

The 2018 blockbuster Crazy Rich Asians is many people’s first and only experience seeing Southeast Asia portrayed onscreen. Kevin Kwan’s enthralling, uber-rich characters jet-set across glittering scenes of cosmopolitan Singapore and paradisiacal beaches in Malaysia. But for Gerald Sim, APARC’s 2016-17 Lee Kong Chian Fellow at the Southeast Asia Program, the scope of cinema in Southeast Asia is much broader than the occasional Hollywood breakout success.

In a new book, Postcolonial Hangups in Southeast Asian Cinema, Sim examines how countries in Southeast Asia navigate the legacies of their unique colonial histories through film media. His writing focuses on Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia and how their cultural identities and postcolonial experiences are stylistically portrayed across commercial films, art cinema, and experimental works.

Sim explores the nuance of these works beyond the typical tropes of hybridity and syncretism in postcolonial identity. His analysis unpacks themes such as Singapore’s preoccupation with space, the importance of sound in Malay culture, and the ongoing investment Indonesia has made into genre and storytelling. Taken together, the book helps situate the regional cinematic traditions and local ideologies in the broader narrative of globalization.

The book builds on research Sim undertook as a fellow at APARC with support from the Lee Kong Chian NUS-Stanford Fellowship on Southeast Asia. He is currently an associate professor of Film and Media Studies at Florida Atlantic University, where he continues to teach about and research the thriving but understudied contributions of Southeast Asian film to world cinema.

Postcolonial Hangups in Southeast Asian Cinemas will be available for purchase from Amsterdam University Press on September 1.

Read Amsterdam University Press' interview with Sims about the book.

Lee Kong Chian Fellowship

Read More

Gerald Sim, a former Lee Kong Chian Fellow with the Southeast Asia Program, explores how Southeast Asian identities, histories, and cultures are portrayed in film in a new book, ‘Postcolonial Hangups in Southeast Asian Cinema.’

Analysis of April 2020 Twitter takedowns linked to Saudia Arabia, the UAE, Egypt, Honduras, Serbia, and Indonesia

On March 11, 2020 Twitter shared with the Stanford Internet Observatory accounts and tweets associated with five distinct takedowns. These include:

- Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Egypt: 5,350 accounts and 36,523,977 tweets. The removed accounts were linked both to a September 2019 takedown of accounts linked to DotDev, a digital marketing firm operating out of Egypt and the UAE, and a December 2019 takedown attributed to Smaat, a Saudi Arabian digital marketing firm. This takedown was a result of a tip the Stanford Internet Observatory shared with Twitter in December 2019.

- Facebook also shared with the Internet Observatory 55 Pages that are linked to this operation; these Pages were run out of Egypt. Facebook attributes these Pages to Maat, a social media marketing firm.

- Egypt (El Fagr newspaper): 2,541 accounts and 7,935,267 tweets. A takedown of accounts tied to the El Fagr newspaper, an Egyptian weekly tabloid. The removed accounts were linked to an October 2019 takedown of El Fagr’s activities by Facebook.

- Honduras: 3,104 accounts and 1,165,019 tweets. A takedown of accounts linked to a staffer of Honduran president Juan Orlando Hernández.

- Serbia: 8,558 accounts and 43,067,074 tweets. A takedown of accounts linked to the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS), the party of current President of Serbia Aleksandar Vučić. These accounts engaged in inauthentic coordinated activity to promote SNS and Vučić, to attack their political opponents, and to amplify content from news outlets favorable to them.

- Indonesia: 795 accounts and 2,700,296 tweets.

In this post we summarize our analysis of the first four operations. We have also written in-depth whitepapers on the Saudi Arabia/UAE/Egypt, Honduras, Serbia, and Egypt and El Fagr operations, linked at the top of the page.

The Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Egypt operation

In December 2019 the Stanford Internet Observatory alerted Twitter to the hashtag #السراج_خائن_ليبيا (Sarraj the traitor of Libya), a reference to the Libyan Prime Minister’s signing of a maritime agreement with Turkey that angered many regional actors. The hashtag had a suspicious distribution pattern, and was shared alongside infographics linked to an earlier Twitter takedown attributed to digital marketers DotDev. Twitter’s subsequent investigation of this hashtag revealed not just a link between this new network and DotDev, but also a link to Smaat, a Saudi Arabian digital marketing firm that Twitter suspended in December 2019 (SIO’s report on Smaat is here); Twitter believes multiple social media management firms created the accounts in this network. In April 2020 they removed 5,350 accounts, which are the subject of this assessment.

Early appearances of the “Sarraj the Traitor of Libya” hashtag.

On March 25 Facebook shared 55 Pages linked to this network.

Key takeaways from the Saudia Arabia/UAE/Egypt datasets:

- Tweets supportive of Khalifa Haftar - a Libyan strongman who heads the self-styled Libyan National Army - began in 2013. This suggests Saudi Arabia/UAE/Egypt disinformation operations on Twitter targeting Libya began earlier than previously known.

- Accounts claimed to be located in a variety of Middle East and North African countries, with many claiming Sudan. They discussed domestic politics with an anti-Turkey, anti-Qatar, and anti-Iran slant. These countries are geopolitical rivals of Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Egypt.

- Recent posts on the Facebook Pages leveraged the COVID-19 pandemic to push these narratives.

- Many of the accounts tweeted links from a set of domains that purport to be news sites for countries like Algeria and Iran; these sites were all created on the same day and publish content with a similar anti-Qatar, -Turkey, and -Iran slant.

- Prominent narratives included discrediting recent Libyan peace talks, criticizing the Syrian government, criticizing Iranian influence in Iraq, praising the Mauritanian government, and criticism of Huthi rebels in Yemen. (We discuss these in detail in our whitepaper)

- There were several interesting behavioral tactics observed in this Twitter data set:

- Hashtag laundering: A geopolitically aligned news website and YouTube channel ran stories about the DotDev-initiated hashtag, with the intent of making it seem like Libyans were (for example) so hostile to Turkey that an anti-Turkey hashtag was trending in Libya. This coverage was grossly exaggerated; the hashtags did not go viral, and the accounts whose tweets they embedded in their articles were subsequently taken down by Twitter.

- Jingoistic personas: The accounts were exceedingly and passionately patriotic to the point of being comedic caricatures. Their profiles emphasized their pride in their purported country, saying things like (translated) “Emirati and Proud” or “Tunisia is my passion” or “I love you, Sudan.”

A March 24, 2020 post from the now-suspended facebook.com/GulfKnights1 criticizing Qatar in the context of COVID-19.

The Egypt operation

This takedown was attributed to actors linked to the El Fagr newspaper in Egypt. El Fagr has previously been associated with influence operations, possibly on behalf of the Egyptian government, on Facebook and Instagram, which took down a network related to their activity in October 2019.

As with several past influence operations attributed to networks operating out of Egypt (and Saudi Arabia), the content consisted of a mix of auto-generated tweets from religious apps, commercial content, geopolitical news content, as well as subversive political astroturfing pushed by accounts that appear to be personas. The political astroturf identities were often made and deployed for a specific topic, created within a short time period and immediately deployed towards a particular topic with very little additional content.

Key takeaways:

- The topics in this Egypt-attributed data set had high overlap with topics in past Egypt-attributed takedowns: negative content about regional rivals such as Qatar and Iran, positive tone towards the Egyptian government.

- News properties were at the center of this network. Several appeared to be legitimate organizations, such as El Fagr itself, and other outlets based in UAE and Yemen.

- Other handles that appeared to be news outlets were fabricated properties that had Twitter accounts with “news” in the name, but did not appear to be actual news outlets - there were no signs of original content. Additionally, a few used names that tried to create the perception that they were regional affiliates of legitimate news organizations (ie, @Foxnewseurope_f).

- Fabricated personalities were created in batches, some serving as content creators, and others serving as content amplifiers. The creators would tweet “original” messages nearly simultaneously (3-6 accounts would put out the same text but not engage with each other), and then outer networks of “disseminators” would amplify them all.

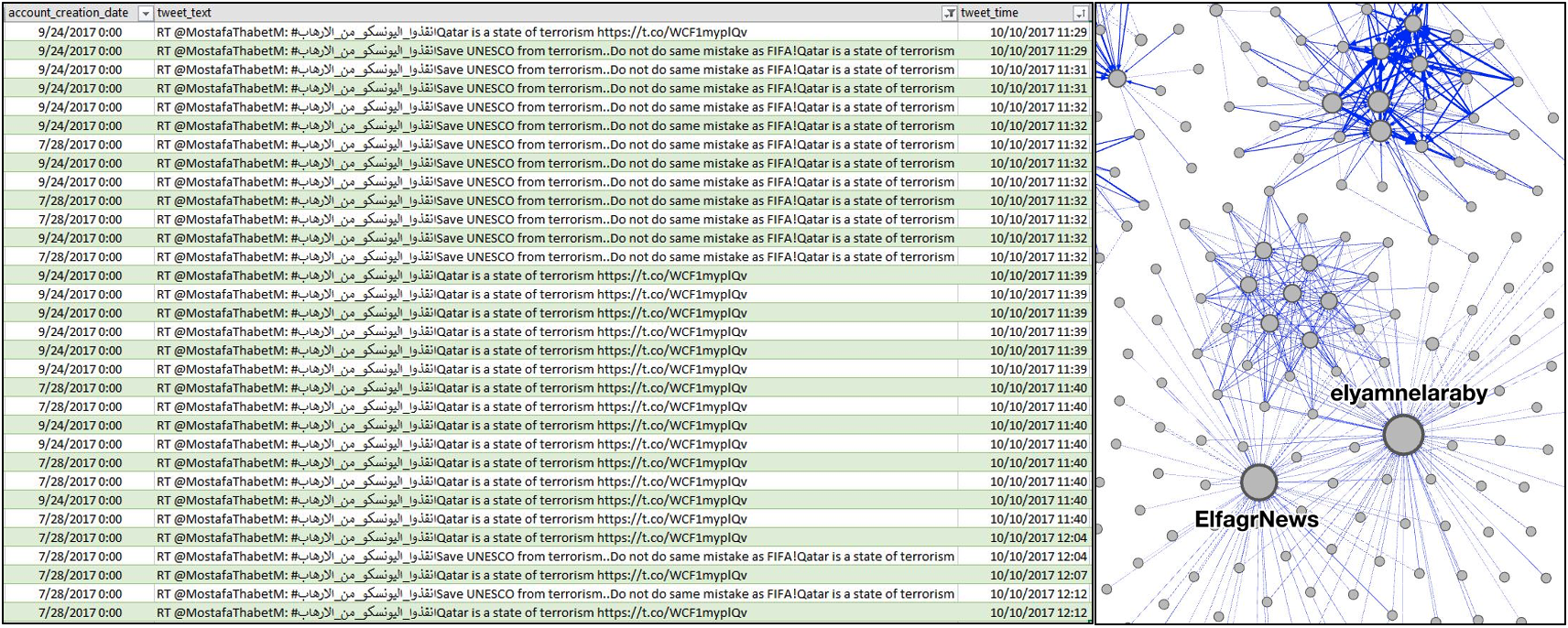

- There was significant amplification of El Fagr’s editor, @MustafaThabetM, with over a hundred thousand retweets - not only from the paper’s own twitter handle, but from a collection of persona accounts. The retweeted content often included sensational or highly political hashtags related to Qatar.

An example of one of the many instances in which networks of accounts created in batches were used to amplify El Fagr’s editor, Mostafa Thabet.

The Honduras operation

This takedown of over 3,000 accounts was attributed to the administration of the Honduran President. and is related to a July 25, 2019 Facebook takedown of 181 accounts and 1,488 Pages. Among the accounts pulled down were those of the Honduran government-owned television station Televisión Nacional de Honduras, several content creator accounts, accounts linked to several presidential initiatives, and some “like-for-likes” accounts likely in the follower-building stage. Much of the tweet behavior seems targeted at drowning out negative news about the Honduran president by promoting presidential initiatives and heavily retweeting the president and news outlets favorable to his administration. Interestingly, a subset of accounts in the dataset are related to self-identified artists, writers, feminists and intellectuals who largely posted tweets critical of the Honduran president Juan Orland Hernandez (‘JOH’).

Tweets by date. A coincides with the Honduran constitutional court permitting presidential re-election; B is the period immediately after the 2017 election; C occurs during the trial of Tony Hernández.

Network graph of all retweets in the dataset. The purple cluster centers on the account of honduran president Juan Orlando Hernández; the turquoise cluster surrounds the account of the Honduran President’s communications office; in pink are news accounts, and green represents what we’re calling the “activista” cluster.

Key Takeaways:

- The Honduras takedown consists of 3,104 accounts and 1,165,019 tweets. 553,211 tweets were original and 611,808 were retweets. Accounts dated as far back as 2008, but roughly two thirds were created in the last year.

- The accounts created in the last year appear largely automated. Their activity overwhelmingly involved retweeting Honduran President @JuanOrlandoH. Approximately 37% of the tweets in the dataset mentioned @JuanOrlandoH.

- The largest removed account was that of Televisión Nacional de Honduras (TNH). The government-controlled TV station’s facebook page was also removed in July 2019. TNH has new social media presence on both platforms as of March 25, 2020.

- Some of the removed accounts are associated with known television and media personalities, one of whom, Chano Rivera, is also a political consultant and publicist.

- The frequency of hashtags including (in translation) #TheNewHonduras, #HondurasAdvances, #BetterLife, #HondurasActivates, #ISupportYouJOH, #LongLiveJOH and #HondurasIsProgressing shows widespread promotion of the president’s initiatives within the dataset. Minimal mention is made of some major news events, such as the criminal conviction of the president’s brother, Tony Hernandez, suggesting that the tweets sought to drown out negative press.

- A set of roughly a dozen accounts associated with self proclaimed writers, artists and feminists formed a distinct group in the dataset. These accounts were the only accounts heavily critical of the government. They also interacted less with the dominant media landscape and the president than other accounts in the dataset. There does appear to be evidence of coordinated activity across the cluster.

The Serbia operation

One of the takedowns announced on April 2, 2020 was a large cluster of Serbian accounts. These accounts were primarily engaged in cheerleading current Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić and his allies, in attacking the Serbian opposition, and in artificially boosting the popularity of Vučić-aligned tweets and content. Among other things, the accounts appear to have focused on supporting Vučić’s run for president in 2017 and tamping down public support for the opposition-led protests known as “1 of 5 Million,” which began in late 2018.

One of the most popular accounts in the Serbia-related takedown, @belilav11, replying to a tweet from the Serbian Progressive Party, the party of current Serbian president Aleksandar Vučić: “The government belongs to the people, not to the yellow tycoons [i.e., the opposition] and their mentors from the west. The people decide in the election who will be in power.” Accounts like this one tweeted in support of Vučić and his allies and attacked the Serbian opposition.

Key takeaways

- The network consisted of approximately 8,558 accounts. While many of these accounts existed earlier, most of the network’s activity came in 2018 and 2019. The accounts sent more than 43 million tweets altogether.

- The accounts served as a coordinated pro-Vučić brigade on Twitter. They tweeted constantly in support of Vučić—over 2 million tweets were sent with the hashtags #Vucic and #vucic—and derided his rivals and the “1 in 5 Million” protests.

- The accounts worked steadily to direct Twitter users to pro-Vučić news sources. Among their tweets were over 8.5 million links to sns.org.rs, informer.rs, alor.rs, and pink.rs, the official site of Vučić’s party and three Vučić-aligned news sites, respectively.

- The accounts relied on a few core tactics to boost visibility and achieve their aims:

- Dogpiling onto opposition-related content. Tweets by opposition politicians and publications were swarmed by the accounts, which replied with critical or derisive comments to give the content the appearance of unpopularity.

- Taking over opposition-related hashtags. When protesters popularized the hashtags #1od5miliona and #PočeloJe, the accounts attacked the originators and attempted to co-opt the hashtags with pro-Vučić content.

- Retweeting Vučić-aligned accounts to boost their popularity. The accounts retweeted @avucic 1.7 million times, @sns_srbija (the official account for Vučić’s party) over 4.5 million times, and @InformerNovine (an SNS-aligned newspaper) over 1.8 million times. Many accounts were engaged solely in retweeting @avucic.

While a precise connection between this network and SNS has not been established, there can be no doubt, given the content these accounts shared and the time period in which they were active, that this network was aligned with Vučić’s efforts to entrench himself and his party in power.

The broad spectrum of takedowns in the April 2020 collection serves as a reminder that coordinated inauthentic behavior manifests globally, comes from a range of actor types, is reliant on broadcast media as well as the social media ecosystem, and that determined manipulators regenerate networks and update tactics with regularity.

4/2/2020, 11:30AM PST: THIS POST WAS UPDATED TO INCLUDE ADDITIONAL INFORMATION FROM FACEBOOK

Between Hope and Caution: One American’s View of Indonesia’s Election

Indonesia’s latest and current experiment with democracy is twenty years old. The fifth national election to be held during that period is set to occur on 17 April 2019. More than 190 million Indonesians are eligible to vote. Those who do will elect the country’s president and vice-president and legislators at four different levels—national, provincial, district, and municipal. Since the collapse of General Suharto’s authoritarian regime in 1998, there have been no coups, and the process of campaigning and balloting every five years has proven to be peaceful with remarkably few and small exceptions. So far so good.

Regarding the top slot, this fifth election is a re-run of the fourth. In 2014, Joko Widodo (“Jokowi”) ran for president against Prabowo Subianto and won. The two men face each other again. For the 2019 race, Jokowi picked Mar’uf Amin to be his vice-president; Prabowo picked Sandiaga Uno to be his. All four men are Muslims.

Compared with Prabowo, Jokowi is a man of the people. Jokowi is the first-ever Indonesian president with a non-elite background. His first career was not in politics, and not in Indonesia’s megalopolis and capital, Jakarta, but in small business in Central Java. He made and sold wood furniture in Surakarta, a city a fraction of Jakarta’s size. He benefited from having begun his political career as Surakarta’s first directly elected mayor. That post afforded him face-to-face contact with his constituents and gained him popularity based on his success in reforming governance, reducing corruption, and improving public services.

Jokowi burnished that reputation as the elected governor of Jakarta. Among his accomplishments on that larger scale were socioeconomic betterment and attention to public transportation. Construction of Indonesia’s very first subway system began in Jakarta on Jokowi’s watch. To his political advantage, the project’s first phase—ten miles of underground and elevated track—was completed and opened to the public in March 2019 mere weeks before the national election in April.

Prabowo’s father was a leading figure in Indonesia’s economy, diplomacy, and politics. Prabowo was schooled in Europe before returning to Indonesia to embark upon a 24-year career in the army. He rose to the rank of a lieutenant general, but his record was marred by association with violence and insubordination. Especially brutal were his roles in crushing movements for independence from coercive Indonesian rule in East Timor and Papua and in the abusive repression of democracy activists during riots in Jakarta in 1998. When Indonesia transitioned to democratic rule later that year, he was, in effect, dishonorably discharged. In 2000 he was denied an American visa, apparently on human rights grounds. Upon leaving the military, Prabowo began a lucrative career in business. He lost the 2014 presidential election to Jokowi, 47-to-53 percent.

Indonesian Presidential candidate Prabowo Subianto addresses to his supporters at the Kridosono stadium during election campaign rally on April 8, 2019 in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Photo by Ulet Ifansasti/Getty Images

Indonesian Presidential candidate Prabowo Subianto addresses to his supporters at the Kridosono stadium during election campaign rally on April 8, 2019 in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Photo by Ulet Ifansasti/Getty Images

Muslims account for an estimated 87 percent of the 269 million people who live in Indonesia, the world’s fourth largest country and the third largest democracy after India and America. It is mathematically understandable that majoritarian Muslim faith and sentiment might drive the country’s politics. But Indonesia is not an Islamic state. Its leaders have, more or less effectively, curated an ethno-religiously plural national identity that legitimates not only Islam but, in theory, Buddhist, Catholic, Confucian, Hindu, and Protestant beliefs as well.

When Jokowi ran for governor of Jakarta in 2012, his running mate was Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, an ethnic-Chinese Christian Indonesian better known by his nickname “Ahok.” When the ticket won, Ahok became vice-governor. A man of probity and candor with a background in business and science, Ahok quickly earned kudos for his efforts to curb poverty, corruption, and traffic congestion, among other ills of the metropolis. In 2014, when Jokowi took a leave of absence to run for president, Ahok replaced him as the acting governor of Jakarta. When Jokowi defeated Pabowo to become president later that year, Ahok became governor in his own right—the first-ever ethnic Chinese and the first non-Muslim in half a century to fill that position. Sinophobia has a long history in Indonesia. In the context of the economic and political crises that obliged Suharto to resign in 1998, for example, anti-Chinese mobs ran riot in Jakarta. Prabowo, Suharto’s son-in-law at the time, may have been at least indirectly involved in that outbreak of racial violence.

In a speech in September 2016, Ahok made an unscripted reference to the possibility that, were he to run again, some Muslims might not vote for him. But all he said was that voters should not believe those who intentionally lie about—misinterpret—verse 51 in Al-Ma’idah, a chapter in the Qur’an that seems to advise Muslims against becoming allies of Jews and Christians. Some Islamists had indeed glossed that verse as an obligation for Muslims not to vote for a non-Muslim to occupy public office. An edited version of the video made it sound as though Ahok were not accusing some people of lying about what the verse meant, but was instead blaming the falsehood on the Qur’an itself—Allah’s own words.

The altered video went viral. Extreme Islamist organizations pressed for Ahok’s arrest and imprisonment for having violated Indonesia’s law on the Misuse and Insult of Religion. He was tried, sentenced, and incarcerated in May 2017.

A man is draped with a flag showing the images of Indonesian President Joao Widodo and his Vice Presidential running mate Ma'ruf Amin at a concert and political rally for President Joko Widodo. Photo by Ed Wray/Getty Images

Ahok regained his freedom in January 2019. When he was released, Jokowi’s and Prabowo’s presidential campaigns had already begun. Six months before, Jokowi’s partisan allies, knowing how closely associated with Ahok their candidate had been, had persuaded him to strengthen his Islamic appeal by choosing Mar’uf Amin to fill the vice-presidential slot on his ticket. At the time, Amin chaired Indonesia’s if not the world’s largest independent Islamic organization, Nahdlatul Ulama. Amin also headed a state-supported Indonesian Ulama Council that issues rulings ( fatwa ) on Islamic matters. Under Amin’s leadership in November 2016, the Council had gone so far as to insist, in a statement he signed on the Council’s behalf, that verse 51 in Al-Ma’idah really does forbid Jews and Christians from becoming leaders and does obligate Muslims to choose to be led only by Muslims—and that to deny this is to insult the Qur’an, the ulama, and the Muslim community. Yet there is nothing in Indonesia’s constitution or its laws that endorses, let alone requires, prejudicial voting—ballot-box communalism—of this kind.

Beyond boosting Jokowi’s image in the eyes of illiberal Muslims, Amin was an attractive choice for two other reasons as well: NU’s demographic strength, notably in the heavily populated provinces of East and Central Java; and the hoped-for gravitas of Amin’s age and wisdom that some voters might read into his being 76 years old on election day—seventeen more than Jokowi’s 58.

In choosing Sandiago (“Sandi”) Uno for the vice-presidential slot on his ticket, Prabowo may also have taken age into account, but in the reverse direction. Sixty-seven years old on election day, Prabowo may have chosen his running mate hoping to benefit from the image of relatively youthful energy and savvy modernity that Sandi, eighteen years younger, might evoke in voters’ minds. Not to mention Sandi’s money. Forbes Magazine ranked him 27 th among the 40 richest Indonesians in 2010, although he has since fallen off that list. Sandi’s proven ability to attract support, having been elected vice-governor of Jakarta in 2017, likely also favored his selection.

Sandi has an MBA from George Washington University. Whatever he learned about good business practices while there, however, did not prevent his name from surfacing in the “Paradise Papers” and in research by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, sources that linked him to shell companies registered in Panama, the British Virgin Islands, and other tax-haven locations.

Sandiaga Uno, Vice-Presidential candidate and running mate of Indonesian Presidential candidate Prabowo Subianto Waves to supporters after giving a speech at the National Stadium on April 7, 2019 in Jakarta, Indonesia. Photo by Ed Wray/Getty Images.

Prabowo did not excel in his televised debates with Jokowi. The many polls conducted again and again during the campaign showed Jokowi ahead of Prabowo in the public’s opinion by as much as twenty percent. As election day neared, the gap between the two men may have narrowed. But that evidence may have been tainted by unreliable polls that Prabowo’s camp may have incentivized to exaggerate his support. [1]

Prabowo has in the past cultivated relations with Islamist figures and groups. A question to be settled on 17 April is whether Jokowi’s supporters among softer-line, mainstream Muslims and their associations will outvote the harder-line Islamist and more Sinophobic voters to whom Prabowo has appealed. Relevant, too, is the credulity of voters regarding fake news on social media, including hoaxes designed to stoke fears of Chinese immigration. One viral claim blamed Jokowi for welcoming investments from China to the point of making Indonesians compete for jobs with an influx of as many as ten million China-born workers. If official Indonesian data are accurate, of 95,335 foreign workers in the country in 2018, only 32,000 were from China. [2]

In the past, Indonesia has been lauded for exemplifying the compatibility of Islam and democracy and for cultivating ethnic tolerance as well. For democracy to survive and succeed, however, as Americans are learning, it must be continually safeguarded and reconfirmed. One of the concepts that will crucially affect the further institutionalization of democracy in Indonesia is the extent to which its large and ethnically Malay Muslim majority will be accountable to the country as a whole and not be demagogued into violating minority rights and freedoms. A populist who inflames his partisan base should not enjoy immunity from oversight. Crucial, too, is the notion of a loyal opposition whose leader is willing and able to reaffirm allegiance to a system in which it has just lost an election fairly. Additionally essential to the implementation of these core ideas, as polarized Americans are being reminded, is the empathy necessary to bridge identity-based cleavages by imagining oneself in the shoes or sandals of “the other.”

In any event, one can hope for the best: that the fifth electoral testing of Indonesia’s two-decades-long experiment with democratic rule in 2019, and the 59th American presidential election in 2020, including their respective aftermaths, will reinvigorate the purpose and power of democratic principles as inoculations against the risks, in both countries, of authoritarian division from within.

Donald K. Emmerson last visited Indonesia in December 2018 to speak at the 11th Bali Democracy Forum. Without implicating them in the above, he is grateful to Bill Liddle, Wayne Forrest, and Lisa Lee for helpful comments on its first draft.

[2] Amy Chew, “‘Let’s Copy Malaysia’: Fake News Stokes Fears for Chinese Indonesians,” South China Morning Post , 7 April 2019, https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/politics/article/3004909/indonesia-election-anti-beijing-sentiments-spread-will-chinese .

The Double-Edged Sword of Palm Oil

Widespread cultivation of oil palm trees has been both an economic boon and an environmental disaster for tropical developing-world countries. New research points to a more sustainable path forward through engagement with small-scale producers.

Nearly ubiquitous in products ranging from cookies to cosmetics, palm oil represents a bedeviling double-edged sword. Widespread cultivation of oil palm trees has been both an economic boon and an environmental disaster for tropical developing-world countries, contributing to large-scale habitat loss, among other impacts. New Stanford-led research points the way to a middle ground of sustainable development through engagement with an often overlooked segment of the supply chain (read related overview and research brief).

"The oil palm sector is working to achieve zero-deforestation supply chains in response to consumer-driven and regulatory pressures, but they won’t be successful until we find effective ways to include small-scale producers in sustainability strategies,” said Elsa Ordway, lead author of a Jan. 10 Nature Communications paper that examines the role of proliferating informal oil palm mills in African deforestation. Ordway, a postdoctoral fellow at The Harvard University Center for the Environment, did the research while a graduate student in Stanford’s School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences.

An oil palm plantation in Cameroon (Image credit: Elsa Ordway)

Using remote sensing tools, Ordway and her colleagues mapped deforestation due to oil palm expansion in Southwest Cameroon, a top producing region in Africa’s third largest palm oil producing country (read about related Stanford research). Contrary to a widely publicized narrative of deforestation driven by industrial-scale expansion, the researchers found most oil palm expansion and associated deforestation occurred outside large, company-owned concessions, and that expansion and forest clearing by small-scale, non-industrial producers was more likely near low-yielding informal mills, scattered throughout the region. This is strong evidence that oil palm production gains in Cameroon are coming from extensification instead of intensification.

Possible solutions for reversing the extensification trend include improving crop and processing yields by using more high-yielding seed types, replanting old plantations, and upgrading and mechanizing milling technologies, among other approaches. To prevent intensification efforts from inciting further deforestation, they will need to be accompanied by complementary natural resource policies that include sustainability incentives for smallholders.

In Indonesia, where a large percentage of the world’s oil palm-related forest clearing has occurred, a similar focus on independent, smallholder producers could yield major benefits for both poverty alleviation and environmental conservation, according to a Jan. 4 Ambio study led by Rosamond Naylor, the William Wrigley Professor in the School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences and a senior fellow at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment and the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies(Naylor coauthored the Cameroon study led by Ordway).

Using field surveys and government data, Naylor and her colleagues analyzed the role of small producers in economic development and environmental damage through land clearing. Their research focused on how changes in legal instruments and government policies during the past two decades, including the abandonment of revenue-sharing agreements between district and central governments and conflicting land title authority among local, regional and central authorities, have fueled rapid oil palm growth and forest clearing in Indonesia.

They found that Indonesia’s shift toward decentralized governance since the end of the Suharto dictatorship in 1998 has simultaneously encouraged economic development through the expansion of smallholder oil palm producers (by far the fastest growing subsector of the industry since decentralization began), reduced rural poverty, and driven ecologically destructive practices such as oil palm encroachment into more than 80 percent of the country’s Tesso Nilo National Park.

A worker in East Kalimantan, Indonesia, loads palm fruit for transport to a factory that will process it into palm oil (Image credit: Joann de Zegher)

A worker in East Kalimantan, Indonesia, loads palm fruit for transport to a factory that will process it into palm oil (Image credit: Joann de Zegher)

A worker in East Kalimantan, Indonesia, loads palm fruit for transport to a factory that will process it into palm oil (Image credit: Joann de Zegher)

Among other potential solutions, Naylor and her coauthors suggest Indonesia’s Village Law of 2014, which devolves authority over economic development to the local level, be re-drafted to enforce existing environmental laws explicitly. Widespread use of external facilitators could help local leaders design sustainable development strategies and allocate village funds more efficiently, according to the research. Also, economic incentives for sustainable development, such as an India program in which residents are paid to leave forests standing, could make a significant impact.

There is reason for hope in recent moves by Indonesia’s government, including support for initiatives that involve large oil palm companies working with smallholders to reduce fires and increase productivity; and the mapping of a national fire prevention plan that relies on financial incentives.

“In all of these efforts, smallholder producers operating within a decentralized form of governance provide both the greatest challenges and the largest opportunities for enhancing rural development while minimizing environmental degradation,” the researchers write.

Coauthors of “Decentralization and the environment: Assessing smallholder oil palm development in Indonesia” include Matthew Higgins, a research assistant at Stanford’s Center on Food Security and the Environment; Ryan Edwards of Dartmouth College, and Walter Falcon, the Helen C. Farnsworth Professor of International Agricultural Policy, Emeritus, at Stanford.

Coauthors of “Oil palm expansion at the expense of forests in Southwest Cameroon associated with proliferation of informal mills” include Raymond Nkongho, a former fellow at Stanford’s Center for Food Security and the Environment; and Eric Lambin, the George and Setsuko Ishiyama Provostial Professor in the School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences and a senior fellow at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment.

Decentralization and the environment: Assessing smallholder oil palm development in Indonesia

Indonesia’s oil palm expansion during the last two decades has resulted in widespread environmental and health damages through land clearing by fire and peat conversion, but it has also contributed to rural poverty alleviation. In this paper, we examine the role that decentralization has played in the process of Indonesia’s oil palm development, particularly among independent smallholder producers. We use primary survey information, along with government documents and statistics, to analyze the institutional dynamics underpinning the sector’s impacts on economic development and the environment. Our analysis focuses on revenue-sharing agreements between district and central governments, district splitting, land title authority, and accountability at individual levels of government. We then assess the role of Indonesia’s Village Law of 2014 in promoting rural development and land clearing by fire. We conclude that both environmental conditionality and positive financial incentives are needed within the Village Law to enhance rural development while minimizing environmental damages.

Indonesian Foreign Policy: Between Two Reefs Again?

The National Monument in Jakarta City, Indonesia. Photo: Ali Trisno Pranoto via Getty Images.

Antje Missbach

The moderates’ dilemma: obstacles to mobilization against Islamist extremism

Abstract: Why do moderate majorities often fail to coordinate opposition to extremist minorities? This paper offers an explanation for the microfoundations of moderate mobilization in the face of extremist minorities using the case of Islamist extremism in Indonesia. In particular, I show that moderates and extremists face asymmetric costs in the decision to voice their true preferences resulting in a coordination dilemma for moderates, which I call the “Moderates’ Dilemma.” An original survey experiment and observational data of participant behavior during two additional surveys demonstrate that moderates hide anti-violent views for fear of reputation costs and that these effects vary by individuals’ sensitivity to reputation costs and degree of uncertainty of others’ attitudes. These findings suggest that over 16 million Indonesians may be hiding moderate preferences and have significant implications for countering violent extremism policies globally.

Speaker Bio: Kerry Ann Carter Persen is a Carnegie Predoctoral Fellow at CISAC for the 2017-2018 academic year and a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of Political Science at Stanford University. Her research focuses on the impact of violent extremism on political behavior in the Islamic World.