Russia's War on Ukraine: A "Teach In" with Michael McFaul

Stanford students are invited to a question-and-answer session with Professor Michael McFaul about the current war in Ukraine. Professor McFaul is a former U.S. ambassador to Russia and the director of the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies. This event is a chance to hear from him directly about Russia's attack on Ukraine, and for students to hear and connect with each other during this urgent crisis.

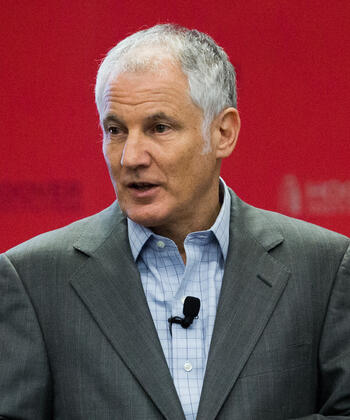

Michael McFaul

Michael A. McFaul

Encina Hall

616 Jane Stanford Way

Stanford, CA 94305-6055

Michael McFaul is Director at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies, the Ken Olivier and Angela Nomellini Professor of International Studies in the Department of Political Science, and the Peter and Helen Bing Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution. He joined the Stanford faculty in 1995. Dr. McFaul also is as an International Affairs Analyst for NBC News and a columnist for The Washington Post. He served for five years in the Obama administration, first as Special Assistant to the President and Senior Director for Russian and Eurasian Affairs at the National Security Council at the White House (2009-2012), and then as U.S. Ambassador to the Russian Federation (2012-2014).

He has authored several books, most recently the New York Times bestseller From Cold War to Hot Peace: An American Ambassador in Putin’s Russia. Earlier books include Advancing Democracy Abroad: Why We Should, How We Can; Transitions To Democracy: A Comparative Perspective (eds. with Kathryn Stoner); Power and Purpose: American Policy toward Russia after the Cold War (with James Goldgeier); and Russia’s Unfinished Revolution: Political Change from Gorbachev to Putin. He is currently writing a book called Autocrats versus Democrats: Lessons from the Cold War for Competing with China and Russia Today.

He teaches courses on great power relations, democratization, comparative foreign policy decision-making, and revolutions.

Dr. McFaul was born and raised in Montana. He received his B.A. in International Relations and Slavic Languages and his M.A. in Soviet and East European Studies from Stanford University in 1986. As a Rhodes Scholar, he completed his D. Phil. In International Relations at Oxford University in 1991. His DPhil thesis was Southern African Liberation and Great Power Intervention: Towards a Theory of Revolution in an International Context.

![Oleksandr Sereda [left] and Artem Romaniukov [right] during their campaigns for, respectively, city council and mayor in Dnipro, Ukraine in the summer of 2020.](https://fsi9-prod.s3.us-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/styles/717x490/public/artem_romaniukov_ukraine_mayor.jpg?itok=AHyGRtgy)

![Oleksandr Sereda [left] and Artem Romaniukov [right] during their campaigns for, respectively, city council and mayor in Dnipro, Ukraine in the summer of 2020.](https://fsi9-prod.s3.us-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/styles/1300x1300/public/artem_romaniukov_ukraine_mayor.jpg?itok=pgwenUv9)

Dean Winslow flying L-39C, April 2019

Dean Winslow flying L-39C, April 2019

Dean Winslow with Maj Bob Coffman with F-15B after flying NATO mission, RAF Lossiemouth (Scotland), 1990.

Dean Winslow with Maj Bob Coffman with F-15B after flying NATO mission, RAF Lossiemouth (Scotland), 1990.