There are 30 civil wars underway around the globe, where civilians are dealing with death and destruction as well as public health emergencies exacerbated by the deadly march of conflict.

Yemen is battling an unprecedented cholera outbreak which has killed more than 2,150 people this year, with another 700,000 suspected cases of the water-borne disease. The government and a rival faction have been fighting for control of the country, taking 10,000 lives since 2015.

Some 17 children in Syria have been paralyzed from a confirmed polio outbreak in northeastern districts, with 48 cases reported in a country that had not had a case of polio since 1999. The cases are concentrated in areas controlled by opponents of President Bashar al-Assad.

And in the Democratic Republic of Congo — where the civil war officially ended years ago, but thousands of people still suffer from recurrent uprisings and scant infrastructure — a yellow fever outbreak was met last year with a lack of vaccines. The WHO was forced to give inoculations containing a fifth of the normal dose, providing protection for only one year.

And yet today, of the nearly 200 countries on this planet, only six nations — three rich ones and three poor ones — have taken steps to evaluate their ability to withstand a global pandemic.

“The bottom line is that despite the profound global threat of pandemics, there remains no global health mechanism to force parties to act in accordance with global health interests,” write FSI’s Paul Wise and Michele Barry in the Fall 2017 issue of Daedalus.

“There also persists inherent disincentives for countries to report an infectious outbreak early in its course,” the authors write. “The economic impact of such a report can be profound, particularly for countries heavily dependent upon tourism or international trade.”

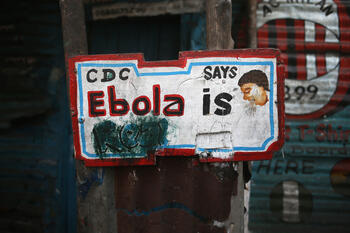

China, for example, hesitated to report the SARS outbreak in 2002 for fear of instability during political transition and embarrassment over early mishandling of the outbreak. Reporting cases of the 2013 Ebola outbreak in West Africa were slow and the virus killed some 11,300 people in Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia before the epidemic was declared over in January 2016.

“Tragic delays in raising the alarm about the Ebola outbreak in West Africa were laid at the doorstep of the affected national authorities and the regional WHO committees, which were highly concerned about the economic and social implications of reporting an outbreak,” Wise and Barry write in the journal published by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

The Daedalus issue, “Civil War & Global Disorder: Threats and Opportunity,” explores the

factors and influences of contemporary civil wars. The 12 essays look at the connection of intrastate strife and transnational terrorism, the limited ambitions of intervening powers, and the many direct and indirect consequences associated with weak states and civil wars.

“Wise and Barry, both medical doctors with extensive field experience in violence-prone developing countries, analyze the relationship between epidemics and intrastate warfare,” write FSI’s Karl Eikenberry and Stephen D. Krasner in their introduction to the issue that includes eight essays by Stanford University faculty.

“Their discussion is premised on the recognition that infectious pandemics can threaten the international order, and that state collapse and civil wars may elevate the risk that pandemics will break out,” they wrote.

Eikenberry and Krasner are hosting a panel discussion about the new volume of Daedalus with FSI senior scholars, including Wise and Barry, on Oct. 23. Members of the Stanford community and the public are invited and can RSVP here. Podcasts with the authors will also be available at FSI’s World Class site over the next few weeks.

Prevention, Detection and Response

Barry and Wise believe there is significant technical capacity to ensure that local infectious outbreaks are not transformed into global pandemics. But those outbreaks require some level of organized and effective governance — and political will.

Prevention, detection, and response are the keys to controlling the risk of a pandemic. Yet it’s almost impossible for these to coincide in areas of conflict.

Prevention includes solid immunization programs and efforts to reduce the risk of animal-to-human spillover associated with exposure to rodents, monkeys and bats.

Then, early detection of an infectious outbreak with pandemic potential is crucial, through a methodical surveillance structure to collect and test samples drawn from domestic and wild animals, a capacity sorely lacking in areas of conflict and weak governance.

“Civil wars commonly disrupt traditional means of communication,” they write. “The Ebola virus outbreak in West Africa exposed glaring weaknesses in the global strategy to control pandemic outbreaks in areas with minimal public health capacity.”

New strategies that utilize satellite or other technology to link remote or insecure areas to surveillance are urgently needed, they said.

Then there is the response in countries where civil war not only makes it difficult, but politically treacherous.

In Syria, there had not been a case of polio reported since 1999. In 2013, health workers began to see children with the kind of paralysis that is associated with a highly contagious polio outbreak.

“However, the government and regional WHO office have been intensely criticized for their slow and uneven response,” the authors note, particularly the government’s resistance to mobilizing immunization efforts in areas sympathetic to opposition forces.

Pressure from international health organizations and neighbors in the region ultimately led to the reinstatement of vaccination campaigns throughout Syria.

“The Syrian polio outbreak is an important reminder that health interventions, though technical in nature, can be transformed into political currency when certain conditions are met,” they write. “At the most basic level, the destruction or withholding of essential health capabilities can be used to coerce adversaries into political compliance, if not complete submission.”

Strengthening Global Oversight

The only comprehensive global framework for pandemic detection and control, the authors write, is the International Health Regulations treaty, which was signed in 2005 by 196 member-nations of the World Health Organization to work together for global health security.

The IHR imposed a deadline of 2012 for all states to have in place the necessary capacities to detect, report and respond to local infectious outbreaks. But only a few parties have reported meeting these requirements, and one-third has not even begun the process. There have also been efforts to enhance state reporting of health systems capacities through voluntary assessments of countries working through the Global Health Security Agenda consortium.

But both frameworks, Barry said in an interview, need financial and political support.

“I see a stronger IHR with more than words — but actual money behind it in order for it to become stronger,” said Barry, noting the Global Health Security Agenda ends in 2018 and she has been asked to sit on a NAAS task force to form its next iteration. “I’m hoping we can move the needle to put money into bio-surveillance and health security, especially in conflict areas.”

Why should Americans care?

“Pathogens know no borders,” Barry said. “And with climate change, we have tremendous movement of vectors; with globalization and billions of people routinely in flight, we have tremendous health threats traveling first class and coach.”

Twenty Countries at High Risk

Meanwhile, some 20 countries are at high risk for pandemic emergence. The two Stanford professors are urgently calling for “new approaches that better integrate the technical and political challenges inherent in preventing pandemics in areas of civil war.”

Wise and Barry note that human factors, such as the expansion of populations into previously forested areas, domesticated animal production practices, food shortages, and alterations in water usage and flows, have been the primary drivers of altered ecological relationships.

So globalization with climate change brews the perfect storm.

“There is substantial evidence that climate change is reshaping ecological interactions and vector prevalence adjacent to human populations,” they said. “Enhanced trade and air transportation have increased the risk that an outbreak will spread widely. While infectious outbreaks can be due to all forms of infectious agents, including bacteria, parasites, and fungi — viruses are of the greatest pandemic concern.”

Science suggests the greatest danger of pandemic lies in tropical and subtropical regions where human and animals are most likely to interact. Most of the estimated 400 emerging infectious diseases that have been identified since 1940 have been zoonoses, or infections that have been transmitted from animals to humans. The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), for example, is believed to have emerged from a simian host in Central Africa.

Recent analyses have suggested that the “hotspots” for emerging infectious diseases overlap substantially with areas plagued by civil conflict and political instability.

The U.S. Agency for International Development and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have been working on the Emerging Pandemic Threats Program to improve local pandemic detection and response capacities by directing resources and training to countries thought to be at high risk for pandemic. However, it is not clear that this and related programs are addressing the political dynamics at the local level that will determine the essential cooperation of local communities with any imposed global health security response.

“The unpredictability of a serious infectious outbreak, the speed with which it can disseminate, and the fears of domestic political audience can together create a powerful destabilizing force,” Wise and Barry write in their conclusion. “Current discussions regarding global health governance reform have largely been preoccupied by the performance and intricate bureaucratic interaction of global health agencies. However, what may prove far more critical may be the ability of global health governance structures to recognize and engage the complex, political realities on the ground in areas plagued by civil war.”