Representing 14 different countries, the Ford Dorsey Master’s in International Policy (MIP) first-year class is a diverse group. Of the 8 men and 21 women, some have worked in government, some have served in the military, and others just completed their undergraduate degrees. Their academic interests range from migration; to clean energy; to women’s, children’s and LGBTQIA rights; and they spend their free time woodworking, practicing Kung Fu, and listening to true-crime podcasts.

The Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies spoke to five of the incoming first-year students about their backgrounds, passions, and dreams for the future. These are their stories.

Serage Amatory, 22. (Chouf, Lebanon)

“I’ve been living in Egypt for the last four years and attending American University in Cairo, where I double-majored in political science and multimedia journalism. My background is in human rights, and I plan to keep working in human rights after school. I worked as a journalist at one of the few nonpartisan TV stations in Lebanon, and I also worked at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Lebanon.

I’ve also made two documentary films — one is about the transgender community in Cairo, and the second film tells the stories of five male victims of rape and sexual assault in Cairo. I enjoy talking about issues that other people don’t want to talk about. I get a lot of disapproval from people all the time, but that's what motivates me — I want to be speaking about people who don’t have someone speaking about them. Someone has to bring attention to things that aren't in the mainstream, and that's what I like to do.

The Master’s in International Policy program here is amazing, and I love that you have the option to specialize in a topic — I’d like to study something concrete and know exactly what I'm going to be doing with it after I graduate. I studied really general topics in undergrad, and now I feel like it's time to augment my general education with something that's more specific. I came in with the expectation that I'm going to be specializing in governance and development, and while I still want to do that, I also really think I might want to take some cyber classes now. So we’ll see — I’m just really happy to be here.”

Maha Al Fahim, 21. (Vancouver, Canada and Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates)

“My interest in public policy started when I was 14. I wrote a nonfiction book about child abuse and gender discrimination, and it was based on my mother's story — she grew up in an abusive family. And in publishing that book, I really saw the power of writing to expose policy issues. When I went to Princeton for my undergraduate education, I wanted to hone my communication skills, because I saw communication as a really powerful tool. I wrote for the Daily Princetonian newspaper and Business Today magazine, and I was also chair of Princeton Writes, a program to promote writing among the community and celebrate the power of words.

Now I'm working on a novel. It's called "Shaolina", and it's set in China. The novel explores gender dynamics and financial and physical power. I traveled to China last summer to do research for the book, and I got to train with a Shaolin monk for 8 hours a day — we would wake up at 5 a.m. and run through the mountains, it was crazy. It was so cool to immerse myself in the experience like that. For me, Kung Fu is not just a sport, it’s a way of life. I've learned so many life lessons from Kung Fu: patience, perseverance, and balance, to name a few.

I love how Stanford is focusing on the future of policy, because as issues get more complex, you need not just qualitative skills, but also quantitative skills. And you need to be able to think creatively and innovatively. Our cohort is small — around 30 students — and I really like it. There are people here from very diverse backgrounds, and it has been really cool to hear so many different international perspectives.”

Angela Ortega Pastor, 25. (Madrid, Spain)

“I studied economics at NYU Abu Dhabi, and then I worked for three years in Paris for the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) as an energy data manager in oil and gas topics. I worked a lot with the different countries within the OECD as well as with other organizations to help collect data, and we put all of that data into comprehensive reports so that other people and companies can use it for analysis. I really liked working there. I liked the international dynamic - everybody came from very different backgrounds and different places, so it was very congenial to learn from other people.

I'm an economist by training, and that impacts the way I like to look at the problems within the energy field. Such as, 'How can we get consumers and companies to want to transition to clean energy? Does it mean that we need to put policies in place, or regulate the market? Or are pure economic incentives going to do the trick?' There are a lot of professors at Stanford who have done research in that sphere, so that was also a big push for me to come here.

I really like Stanford so far. I've found that people here are very welcoming and happy to help. I was a bit worried about that - when you move somewhere new, you sometimes worry about cliques and how focused people will be on their own lives. But everyone that I've encountered has been really nice and helpful. It's made feel like, 'OK - I can figure out how this place works and eventually feel at home.'”

Craig Nelson, 37. (Minneapolis, Minnesota)

“I'm an infantry officer in the U.S. Army. I graduated from West Point in 2006, and I'm in my 14th year of service. I've done eight deployments across both Iraq and Afghanistan, and I've also spent a good amount of time stationed in Europe. My wife, Michelle, and I just moved to Palo Alto from Vicenza, Italy, with our 2-year-old son, Max. Michelle and I love to travel, we love being stationed abroad, and we think that the best way to complete a 20-year career in the Army is to be abroad as much as possible and see parts of the world that we would not otherwise be exposed to.

Overall what I hope to learn here is a better way for the American Army to help to implement the policy that I was a part of as the U.S. Army's forward-deployed unit in Europe. I was able to see where policy derived by our elected officials is actually implemented at a tactical level. I’d like to go back to the Army and implement that policy with a refined understanding of where it comes from and how it's generated.

Before social media became as ubiquitous as it is now, I think people were in groups based largely on where they're from - a certain area code, or a neighborhood, or a school. Now it's possible to identify with a group completely without respect to geographic location, and I think that's because of social media. I'm interested in how that drives security policy - how does that change cyber security policy, and how does that change the way that my country interfaces with its allies and its partners?

When I go back to the Army, I hope to be in a position of greater responsibility and leadership. And I think that this experience will broaden me in a way that I would not have achieved if I had stayed in the operational Army and done a more traditional job following what I just did in Italy.”

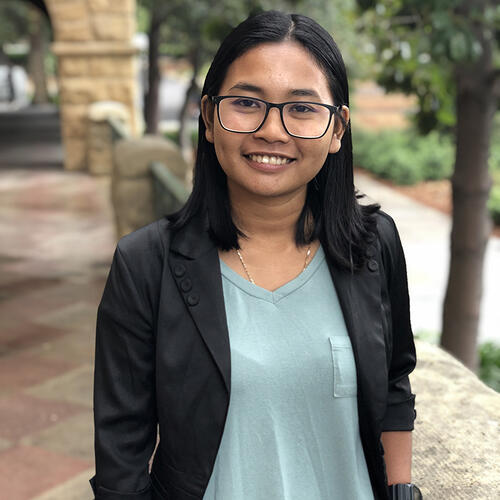

Sievlan Len, 23. (Toul Roveang Village, Cambodia)

“I earned my bachelor’s degree in global affairs from the American University of Phnom Penh in Cambodia. I did two internships before coming to Stanford: one was with a consulting firm, where I was working mainly on migration research and youth participation initiatives at the sub-national level. I also worked for a foundation that works on strengthening political parties in Cambodia. It was a really interesting experience, and it gave me the idea of doing my bachelor's thesis on migration.

My interests right now are in migration, development, and education. And I’m interested to learn about how the three interact, and how we can make the most out of migration. I'm so excited to explore the interdisciplinary aspects of the Master’s in International Policy program, because I've always felt that you can't separate these issues one from another — migration itself is very interdisciplinary, there is both a political and an economic side to it.

I come from a village in Cambodia, and I'm one of the luckiest in that I had the opportunity to pursue higher education. One of my dreams and goals is that everyone in Cambodia — including girls — have equal access to education, and at least to finish high school, and have the opportunity to pursue their dreams in universities if they’d like to. Where I grew up, I saw a lot of potential not being fulfilled because of people’s circumstances — poverty, or elders not valuing education. I really want to see that change. I want everyone to be able to reach their full potential.”