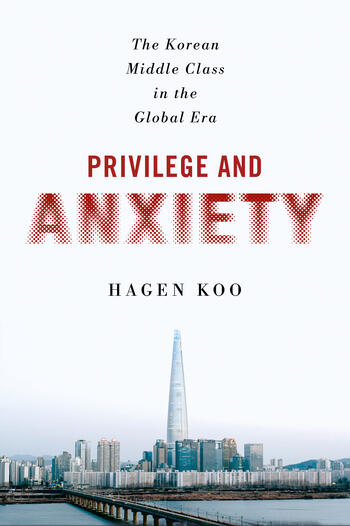

Meet the Ford Dorsey Master's in International Policy Class of 2025

It’s a new academic year at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies (FSI), which means we’re welcoming our new class of the Ford Dorsey Master’s in International Policy!

The Class of 2025 is a cohort of 28 students representing six different states and eleven different countries, including Belgium, China, Indonesia, Japan, Lebanon, Peru, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

These students have come to us from academia, government, NGOs, the private sector, and the military in order to learn more about the frameworks that shape effective policy and for the opportunity to practice those theories hands-on in the Policy Change Studio. From tackling challenges caused by climate change to honing leadership skills for the armed services, the Class of 2025 is ready to get to work!

Keep reading to meet six members of the new cohort and learn more about the projects that have brought them to Stanford.

I’ve been given a lot of unique opportunities in my life, and I’m delighted that coming to Stanford to study cyber policy is the next step in my journey.

My work with cyber has already taken me through the U.S. Army as an intelligence analyst and into tech companies like StubHub and eBay, where I was a financial crime investigator, and Meta, where I worked on investigative teams looking into issues surrounding the 2020 U.S. election, the military coup in Myanmar, Ethiopia's civil war, and the evacuation of Afghanistan.

It’s surreal in the best way to be working with scholars and advisors like Renée DiResta and Alex Stamos whom I’ve read so much research from over the years. Because Stanford is so connected to Silicon Valley, it’s a prime place to look at policy impacts in the private sector. I’ve already had a chance to see public policy close-up, and I want to look more closely at how we can better engage the private sector to bring about societal changes.

One of the places where I think we need to rethink our approach is digital security. I’ve worked a lot on fraud and online crime cases during my career, and we tend to treat those issues very adversarially: reducing either entire nation-states or groups and movements of thousands and millions of people to amorphous, shadowy, dark, evil bad actors lurking in the ether is not a sustainable way to grow as a community and species. There are definitely really bad people out there, and without question there are people who have been exploited, but thinking about the issue in pure diametrics can be very dehumanizing. For every dark web mob boss targeting the innocent, there are a lot of undereducated, marginalized people targeting each other in a basic effort to get by.

I think we need to start asking harder questions about the incentives and root causes that drive people towards these crimes in the first place. Is it a lack of education? A lack of opportunity? The need for more resources? How do we as a society want to deal with those issues? Instead of just playing the whack-a-mole game that digital security currently is, I think the braver approach has to come from understanding the societal factors that create bad actors in the first place. We have to change those paradigms and take on the work of rehabilitating people rather than simply demonizing and dehumanizing them.

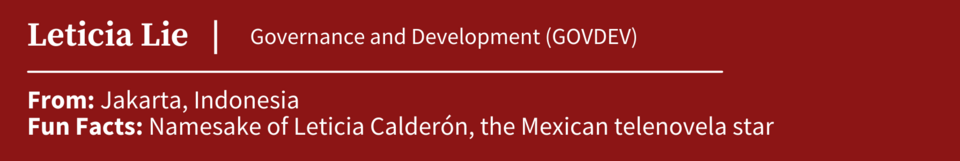

While I was an undergrad studying in Australia, I did volunteer and fundraising work with other Indonesian students. Throughout the semester, we’d collect funds, and then there would be a trip where we would go back to Indonesia and visit the children at the foster house we’d been collecting funds for. Sometimes these kids would go on to go to school or get a job, but their situation always seemed so precarious. If the economy changed or the money stopped, they’d be right back where they started. There wasn’t a good safety net to catch people, and donations were never going to be enough to change the situation for the long-term.

Seeing this made me start thinking about the public sector and how to improve public services that can act as a robust safety net for people in difficult times. Earlier in my career, I was very focused on empirical-based recommendations. I felt that as long as the data was convincing, that would be enough to create change. What I’ve realized is that good policy advice isn’t enough — you also need political will to implement the policy, driven by a well-informed public who can hold their elected policymakers accountable to deliver the changes they wish to see .

However, currently people find it difficult to understand the stances politicians take on certain issues and to keep track of whether they're delivering on their promises during their term in office. There’s not a very well-developed culture of people participating in policy making. I want to find ways of closing that gap between the people and their policy makers.

That’s a massive challenge to tackle, but I know that learning more about governance and political frameworks with my MIP cohort will help me develop skills I can take back to Indonesia. There’s a big emphasis in this program on hands-on learning and experience outside of the classroom. It’s very focused on designing a solution, then testing it in the real world, then going back to redesign and test, redesign and test, until you get something that can actually make a difference. I’m confident that my time here is going to be invaluable for building public participation in Indonesia’s democratic and policymaking process.

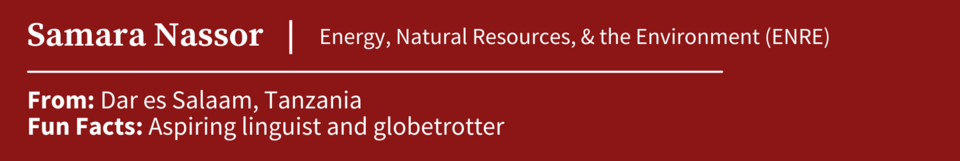

My journey towards climate adaptation and mitigation is deeply personal, shaped by my lived experiences in the coastal cities of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, and Mombasa, Kenya, where I grew up. My mission is to treat climate change as a sustainable development issue and implement policies that holistically alleviate its impacts on vulnerable populations in Sub-Saharan Africa and the world. At Stanford, I hope to explore how science, technology, business, and society can work together to make this possible.

I’ve had the privilege of contributing to the development of renewable energy, water, and land conservation projects at different scales while working for a global non-profit (The Nature Conservancy), a multinational company (Schneider Electric), and an intergovernmental organization (The United Nations). Additionally, I had opportunities to engage in projects that address local problems of environmental and economic insecurity in various towns and villages in Tanzania (Zanzibar and Tanga), Cameroon (Bamenda), and the United States. These opportunities enabled me to collaborate with a wide variety of stakeholders in business, government, and civil society, thereby helping me hone technical and interpersonal skills relevant to the environmental field.

As I continue my studies at Stanford, focusing on international policy, my goal is to channel my experiences, skills, and commitment to creating meaningful change. One of the exciting things about MIP is being amongst a nexus of people with tremendous talent. Tapping into this rich and vibrant community will help transform me as an aspiring leader in the climate space.

Since I was a little kid, I’ve been interested in what’s going on around me, and why things are the way they are. I come from Peru, and in an emerging economy like that it can be more obvious when public services don’t work. Everyone has stories from friends or family or firsthand experience of the difficulties they’ve had in accessing public services. I think that instilled a desire to solve issues of poverty and inequality very early on in my life. I’ve been asking those sorts of questions – What is this system? Why is it this way? How can we make it better? – for a long time.

I’m trained as an economist, but I believe we’ll only be able to find solutions to the major issues facing the world if we take an interdisciplinary approach. Yes, we need economic tools, but we have to combine those with frameworks from political science, international relations, law, education, public health, etc. We have to understand how the institutions who administer these frameworks function, and what we can do to change them when they’re not serving their purpose effectively.

And we also need to be open to learning from each other and making sure many different voices and perspectives are part of these discussions. We especially need young voices and youth participation in public policy. One generation may be in a position to make the policy, but it's the younger generations who will live with them. If we’re not helping them learn now, how can they be effective policy makers later?

I’m looking forward to my time in the MIP program as an opportunity to expand my knowledge and my network and make the kinds of multidisciplinary connections that will make me a more effective leader and mentor. The people here come from so many different backgrounds, and talking with them and learning from them is going to give me even more tools for how to approach these problems.

My work experience is at the intersection of dual-use startups, venture capital, and the federal government. I most recently worked for Booz Allen Ventures, which is the corporate venture capital fund of Booz Allen Hamilton - focused on defense tech startups that can support national security missions. I supported the deal process end-to-end, from sourcing defense tech startups to developing business cases and facilitating value creation for portfolio companies. Prior to that, I supported several Department of Defense (DoD) teams, scouting dual-use startups based on certain use cases and technical requirements. I also conducted research on foreign investment in the U.S. startup ecosystem, assessing foreign influence within specific technology sectors.

My work experience has provided me with a deep understanding of and familiarity with the defense tech sector – both startups with dual-use applications and associated government needs and priorities – and how critical commercial technology is to supporting DoD efforts and ensuring national security.

With rising geopolitical tensions in the world and China positioning as a great power competitor to the U.S., it feels like a great opportunity to be at Stanford and study international security and policy. At Stanford, my research interests revolve around venture capital and dual-use startups that support national security, opportunities/mechanisms to bridge the "valley of death" in the U.S. government, and adversarial capital/foreign investment in the U.S. I was drawn to the MIP program at Stanford because there are so many opportunities to research these areas and study them in depth from leading experts.

The MIP program also has a mission-oriented structure and mindset that really resonates with me. There are programs like the Gordian Knot Center at CISAC and classes like Hacking for Defense that are working in this same space: identifying private sector solutions for public sector needs. I’ve seen how good venture capital investments can accelerate startups that strengthen the DoD, and how good innovation, technology, and defense policy supports national security. I’m excited to continue working on these areas through my time at Stanford.

As an active duty Army officer and Downing Scholar, I intentionally pursued the MIP program at FSI because of the opportunity for personal growth, among the other unique aspects of studying at Stanford. A decade of military service taught me the simple truth that one will experience the most growth in the challenging territories outside of one’s comfort zone. Today, while passionate about International Security or Government & Development (two of the specializations offered by the MIP program), the Cyber Policy and Security track resides the furthest outside of my comfort zone and, therefore, offers me the greatest opportunity for personal growth.

In the military, the geometry of warfighting is divided into domains as a way of organizing and analyzing them. Admittedly, the cyber domain is the one I’m currently least familiar with, but the area that I feel is going to have the biggest effect on my ability to make and influence military decisions in the future. I’ve already witnessed how exponential growth within the cyber domain can expand the array of options for policy makers but, conversely, also create a new front of domestic vulnerability that U.S. national security and democracy is far from immune to. As I continue in my service, I want to be able to provide the best possible recommendations and make the most informed decisions possible. So, I’m here at Stanford to grow, discover and cover my blind spots.

More broadly, I understand this opportunity to reflect on my first decade of service while studying at Stanford is rare and well-timed. Today, I'm at a career-juncture where I’m now expected to understand the policy and strategic purpose behind the operational and tactical tasks at hand. That comes with a lot of responsibility. I’m more frequently in situations where I’m either directly making the decision or being asked, “What do you think about this?” by senior leaders. As a leader at any level, I want to be able to provide the best military advice possible, and I want to have a clear understanding of where my own decisions are coming from. Am I being objective or subjective? Do we have a clear end-state? Are we walking into a familiar and avoidable trap? I know the roots of many of these questions reside in policy. Therefore, I seek to build more of a mental foundation in the development of effective policy through a hands-on educational experience.

Today’s world offers no shortage of international policy problem-sets. One of the reasons the MIP program at FSI was so appealing to me was the environment it creates for hands-on learning opportunities to grapple with some of these problems. Dr. Fukuyama’s Policy Problem-Solving Framework and the MIP’s culminating capstone project offer tangible and solution-based opportunities to hone the skills I’ll take back to the Army. Lastly, Stanford houses a potent mix of people who have been policy practitioners, who have worked in government either here in the U.S. or abroad, and who are leading scholars in their field. Additionally, in this small and talented cohort of 28, another highlight to the MIP is our ability to frequently and directly interact with the faculty leadership and grow together. I’m excited by the opportunity for growth this all creates for me to not only share what I’ve learned in my career so far, but also to have that directly challenged and get feedback from my peers and professors. This experience will undoubtedly be invaluable when the time comes to step back into military service.

The Ford Dorsey Master's in International Policy

Interested in studying international policy? Explore the links to see if the Ford Dorsey Master's in International Policy at Stanford is right for you!

Read More

From tackling challenges caused by climate change to honing leadership skills for the armed services, the Class of 2025 has arrived at Stanford and is ready to get to work.