U.S. Needs a New Approach for Governance of Risky Research

The United States needs to build a better governance regime for oversight of risky biological research to reduce the likelihood of a bioengineered super virus escaping from the lab or being deliberately unleashed, according to an article from three Stanford scholars published in the journal Science today.

"We've got an increasing number of unusually risky experiments, and we need to be more thoughtful and deliberate in how we oversee this work," said co-author David Relman, a professor of infectious diseases and co-director of Stanford's Center for International Security and Cooperation (CISAC).

Relman said that cutting-edge bioscience and technology research has yielded tremendous benefits, such as cheap and effective ways of developing new drugs, vaccines, fuels and food. But he said he was concerned about the growing number of labs that are developing novel pathogens with pandemic potential.

For instance, researchers at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, in their quest to create a better model for studying human disease, recently deployed a gene editing technique known as CRISPR-Cas9 on a respiratory virus so that it was able to edit the mouse genome and cause cancer in infected mice.

"They ended up creating, in my mind, a very dangerous virus and showed others how they too could make similar kinds of dangerous viruses," Relman said.

Scientists in the United States and the Netherlands, conducting so-called "gain-of-function" experiments, have also created much more contagious versions of the deadly H5N1 bird flu in the lab.

Publicly available information from published experiments like these, such as genomic sequence data, could allow scientists to reverse engineer a virus that would be difficult to contain and highly harmful were it to spread.

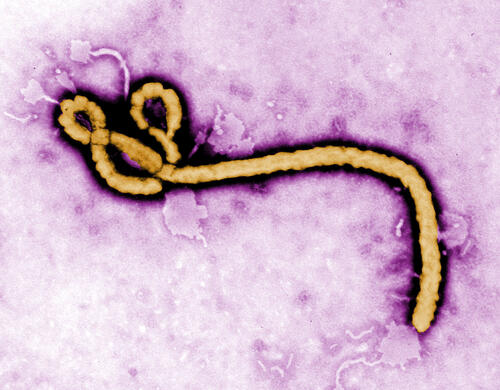

And a recent spate of high-profile accidents at U.S. government labs – including the mishandling of anthrax, bird flu, smallpox and Ebola samples – has raised the specter of a dangerous pathogen escaping from the lab and causing an outbreak or even a global pandemic.

"These kinds of accidents can have severe consequences," said Megan Palmer, CISAC senior research scholar and a co-author on the paper. "But we lack adequate processes and public information to assess the significance of the benefits and risks. Unless we address this fundamental issue, then we're going to continue to be reactive and make ourselves more vulnerable to mistakes and accidents in the long term."

Centralizing leadership

Leadership on risk management in biotechnology has not evolved much since the mid-1970s, when pioneering scientists gathered at the Asilomar Conference on Recombinant DNA and established guidelines that are still in use today.

Palmer said that although scientific self-governance is an essential element of oversight, left unchecked, it could lead to a "culture of invincibility over time."

"There's reliance on really a narrow set of technical experts to assess risks, and we need to broaden that leadership to be able to account for the new types of opportunities and challenges that emerging science and technology bring," she said.

Relman described the current system as "piecemeal, ad hoc and uncoordinated," and said that a more "holistic" approach that included academia, industry and all levels of government was needed to tackle the problem.

"It's time for us as a set of communities to step back and think more strategically," Relman said.

The governance of "dual use" technologies, which can be used for both peaceful and offensive purposes, poses significant challenges in the life sciences, said Stanford political scientist Francis Fukuyama, who also contributed to the paper.

"Unlike nuclear weapons, it doesn't take large-scale labs," Fukuyama said. "It doesn't take a lot of capacity to do dangerous research on biology."

The co-authors recommend appointing a top-ranking government official, such as a special assistant to the president, and a supporting committee, to oversee safety and security in the life sciences and associated technologies. They would coordinate the management of risk, including regulatory authorities needed to ensure accountability and information sharing.

"Although many agencies right now are tasked with worrying about safety, they have got conflicting interests that make them not ideal for being the single point of vigilance in this area," Fukuyama said.

"The National Institutes of Health is trying to promote research but also stop dangerous research. Sometimes those two aims run at cross-purposes.

"It's a big step to call for a new regulator, because in general we have too much regulation, but we felt there were a lot of dangers that were not being responded to in an appropriate way."

Improving cooperation

Strong cooperative international mechanisms are also needed to encourage other countries to support responsible research, Fukuyama said.

"What we want to avoid is a kind of arms race phenomenon, where countries are trying to compete with each other doing risky research in this area, and not wanting to mitigate risks because of fears that other countries are going to get ahead of them," he said.

The co-authors also recommended investing in research centers as a strategic way to build critical perspective and analysis of oversight challenges as biotechnology becomes increasing accessible.