Rosenkranz Prize Winners: Helping Children Grow in Bangladesh and Preventing Blindness in West Africa

Rosenkranz Prize Winners: Helping Children Grow in Bangladesh and Preventing Blindness in West Africa

The Rosenkranz Prize is endowed by the family of Dr. George Rosenkranz to honor his legacy of scientific innovation to improve global health in low- to middle-income countries.

The 2023 Rosenkranz Prize winners both believe their research has the capacity to not only change population health policy one day — but also reduce health disparities in developing countries with low-cost and straight-forward interventions.

The Dr. George Rosenkranz Prize is awarded by the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies and Stanford Health Policy to Stanford researchers of all disciplines doing innovative work to improve health in low- to middle-income countries. It is endowed by the family of the late scientist who devoted his career to improving health-care access across the world.

“Both Jade and Arthur are doing highly innovative work on incredibly complex population health challenges, with the potential for upending traditional approaches in their fields,” said Grant Miller, professor of health policy and chair of the Rosenkranz Prize selection committee. "Their personal commitment as well as their new ways of approaching old challenges, truly exemplify the tradition that Dr. George Rosenkranz and his family have established.”

Preventing Child Stunting in Bangladesh

Jade Benjamin-Chung, PhD, MPH, an assistant professor in the Department of Epidemiology and Population Health at Stanford Medicine, applies causal inference and machine learning tools to investigate ways to control or eradicate infectious diseases such as malaria, diarrhea and parasitic diseases. The epidemiologist spent years working in Haiti, Thailand, Myanmar and Bangladesh, observing first-hand how structural causes of inequality influence disease.

Benjamin-Chung, who is also a Chan Zuckerberg Biohub investigator, will use the $100,000 prize to build on her research into child exposure to soil in the rural homes of Bangladesh. Water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) interventions have been the cornerstone of preventing diarrhea, the second-leading cause of death among children 5 and younger. The dehydration from severe diarrhea kills more than 2,000 children around the world every day — more than AIDS, malaria and measles combined.

According to Stanford research, while WASH interventions do improve overall health, they have not been that successful in preventing stunting among young children. If a child doesn’t grow normally within the first two years, it can impact growth and cognitive functions later in life.

“The disappointing impacts of WASH on child health spurred our team to radically rethink strategies to prevent child soil-transmitted helminth (STH) infection and diarrhea in low- to middle-income countries,” Benjamin-Chung said.

Benjamin-Chung’s investigative team has launched a randomized trial in 800 eligible households in the rural areas of the southeastern Comilla district of Bangladesh, where more than 75% of households have soil floors. Eligible households will include pregnant women in their second or third trimester. The team will install concrete floors starting this June when the birth cohort is still in utero; they will measure health and child development outcomes at ages 6, 12, 18 and 24 months.

Much of life takes place on floors in Bangladesh, such as breastfeeding, infant feeding, cooking and playing. The women in her study said they would prefer smooth, clean concrete floors, but most of them cannot afford the luxury. Benjamin-Chung said that during her research in Bangladesh, she became a mother and now sees these women’s daily lives quite differently.

“I have the privilege of living in a high-income setting with running water, ample cleaning supplies, and importantly, a floor for my children to play on that I can easily clean,” she said. “If installing concrete floors benefits child health, understanding how these benefits occur is key for policy impact. This information is critical for persuading policymakers to fund and scale up health interventions and may inform the design of other child development interventions.”

Preventing Blindness in West Africa

Arthur Brant, MD, a Stanford computer science grad went on to work at Google Life Sciences as a software engineer working on projects ranging from multiple sclerosis genomics to cloud security. Today, he’s an ophthalmology resident at Stanford Medical School.

“I transitioned away from tech in 2017 to start medical school because I felt like I would live a life of greater consequence as a physician,” Brant said.

He became interested in global ophthalmology after meeting Geoffrey Tabin, MD, the co-founder and chairman of the Himalayan Cataract Project and professor of ophthalmology and global medicine at Stanford.

“He frequently remarked on the large burden of untreated sickle cell blindness in West Africa,” Brant said. “But the burden of disease didn’t fully strike me until I spent a day in Dr. Akwasi Ahmed’s retina clinic in Ghana.”

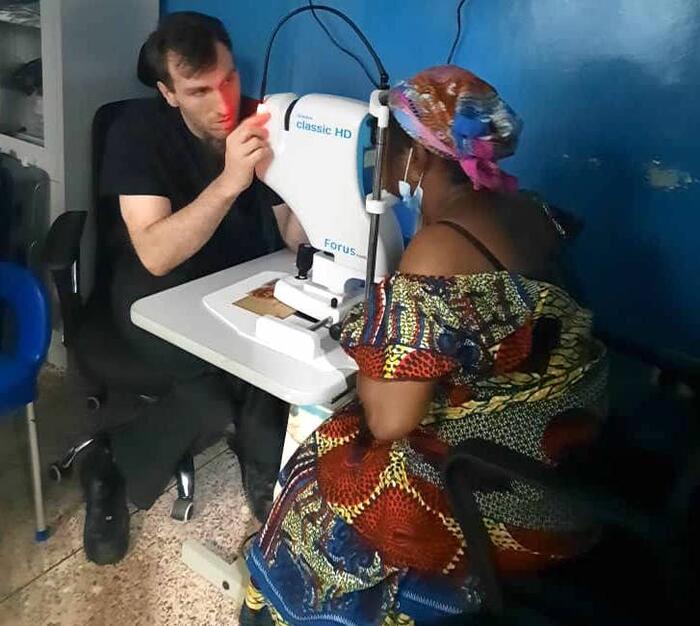

Brant saw numerous cases of young adults who had permanently lost their vision from what’s known as sickle cell retinopathy — a disease that is easily screened and can be treated with laser therapy that takes some 10 minutes.

(Brant takes a photograph with a low-cost retinal camera to screen for diabetic retinopathy and sickle cell retinopathy in the eye clinic in Ghana)

Sickle cell retinopathy, Brant explains, is a complication of sickle cell disease (SCD) and one of the leading causes of retinal blindness in Ghana. The abnormal hemoglobin in sickle cell disease leads to sickle-shaped red blood cells that intermittently occlude blood vessels, which can lead to retinal detachment and blindness. Sickle cell disease is prevalent among West Africans; it’s estimated that some 5 million West Africans will develop SC retinopathy by the age of 20.

“In West Africa, the burden of disease is poorly understood, almost no patients are screened for early treatment, and little can be offered to patients by the time they present to clinic,” said Brant, who has also done ophthalmology research in India, Nepal and Ethiopia.

He intends to use his $100,000 prize to work on finding a safe and practical solution to prevent blindness — with the goal of eliminating blindness from sickle cell in West Africa.

Brant’s Rosenkranz project will build on an existing collaboration with eye center at the Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital in Kumasi, Ghana, where he will design a randomized control trial to determine the optimal treatment for sickle cell.

“Our goal is to reduce or eliminate preventable blindness from SR in West Africa,” Brant said. “Through these studies, we aim to establish the first-ever SR screening and treatment program in West Africa. This program can then be used as a model for other parts of Africa and the developing world.”