Clubhouse in China: Is the data safe?

Clubhouse in China: Is the data safe?

The audio chat app “Clubhouse” went viral among Chinese-speaking audiences. Stanford Internet Observatory examines whether user data was protected, and why that matters.

Last week, the drop-in audio chat app “Clubhouse” enabled rare unfettered Mandarin-language debate for mainland Chinese iPhone users, before being abruptly blocked by the country’s online censors on Monday February 8, 2021.

Alongside casual conversations about travel and health, users frankly discussed Uighur concentration camps in Xinjiang, the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests, and personal experiences of being interrogated by police. The Chinese government restricts open discussion of these topics, maintaining a “Great Firewall” to block domestic audiences from accessing many foreign apps and websites. Although last week Clubhouse had not yet been blocked by the Great Firewall, some mainland users worried the government could eavesdrop on the conversation, leading to reprisals.

In recent years, the Chinese government under President Xi Jinping has shown an increased willingness to prosecute its citizens for speech critical of the regime, even when that speech is blocked in China. Clubhouse app’s audio messages, unlike Twitter posts, leave no public record after speech occurs, potentially complicating Chinese government monitoring efforts.

The Stanford Internet Observatory has confirmed that Agora, a Shanghai-based provider of real-time engagement software, supplies back-end infrastructure to the Clubhouse App (see Appendix). This relationship had previously been widely suspected but not publicly confirmed. Further, SIO has determined that a user’s unique Clubhouse ID number and chatroom ID are transmitted in plaintext, and Agora would likely have access to users’ raw audio, potentially providing access to the Chinese government. In at least one instance, SIO observed room metadata being relayed to servers we believe to be hosted in the PRC, and audio to servers managed by Chinese entities and distributed around the world via Anycast. It is also likely possible to connect Clubhouse IDs with user profiles.

SIO chose to disclose these security issues because they are both relatively easy to uncover and because they pose immediate security risks to Clubhouse’s millions of users, particularly those in China. SIO has discovered other security flaws that we have privately disclosed to Clubhouse and will publicly disclose when they are fixed or after a set deadline.

In this blog post, we investigate the possibility of Chinese government access to Clubhouse audio, both via Agora and Clubhouse app itself. We also explore why that might matter. We will address these key issues:

What is Agora, how do we know it provides back-end support to Clubhouse, and why does that matter?

Can the Chinese government access audio stored by Clubhouse?

Are mainland Chinese users likely to face reprisals for speech on the app?

What is Agora, how do we know it provides back-end support to Clubhouse, and why does that matter?

What is Agora?

Agora is a Shanghai-based start-up, with U.S. headquarters in Silicon Valley, that sells a “real-time voice and video engagement” platform for other software companies to build upon. In other words, it provides the nuts-and-bolts infrastructure so that other apps, like Clubhouse, can focus on interface design, specific functionalities, and the overall user experience. If an app operates on Agora’s infrastructure, the end-user might have no idea.

How do we know it provides back-end support to Clubhouse?

SIO analysts observed Clubhouse’s web traffic using publicly available network analysis tools, such as Wireshark. Our analysis revealed that outgoing web traffic is directed to servers operated by Agora, including “qos-america.agoralab.co.” Joining a channel, for instance, generates a packet directed to Agora’s back-end infrastructure. That packet contains metadata about each user, including their unique Clubhouse ID number and the room ID they are joining. That metadata is sent over the internet in plaintext (not encrypted), meaning that any third-party with access to a user’s network traffic can access it. In this manner, an eavesdropper might learn whether two users are talking to each other, for instance, by detecting whether those users are joining the same channel.

An SIO analysis of Agora’s platform documentation also reveals that Agora would likely have access to Clubhouse’s raw audio traffic. Barring end-to-end encryption (E2EE), that audio could be intercepted, transcribed, and otherwise stored by Agora. It is exceedingly unlikely that Clubhouse has implemented E2EE encryption.

We expand on the technical details of these findings in the technical analysis appendix at the end of this post.

Why does Agora’s hosting of Clubhouse traffic matter?

Because Agora is based jointly in the U.S. and China, it is subject to People’s Republic of China (PRC) cybersecurity law. In a filing to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, the company acknowledged that it would be required to “provide assistance and support in accordance with [PRC] law,” including protecting national security and criminal investigations. If the Chinese government determined that an audio message jeopardized national security, Agora would be legally required to assist the government in locating and storing it.

Conversations about the Tiananmen protests, Xinjiang camps, or Hong Kong protests could qualify as criminal activity. They have qualified before.

Agora claims not to store user audio or metadata, except to monitor network quality and bill its clients. If that is true, the Chinese government wouldn’t be able to legally request user data from Agora — Agora would not have any records of user data. However, the Chinese government could still theoretically tap Agora’s networks and record it themselves. Or Agora could be misrepresenting its data storage practices. (Huawei, a large Chinese software company with close links to the country’s military, also claims not to hand data to the government. Many experts are doubtful.)

Further, any unencrypted data that is transmitted via servers in the PRC would likely be accessible to the Chinese government. Given that SIO observed room metadata being transmitted to servers we believe to be hosted in the PRC, the Chinese government can likely collect metadata without even accessing Agora’s networks.

In summary, if the Chinese government can access user data via Agora, mainland Chinese users of Clubhouse could be at risk. It is important to keep in mind, however, that having the potential to access user data is not the same as actually accessing it. The Chinese government is a large and sometimes unwieldy bureaucracy, just like the U.S. government. It is easy to overstate the Chinese government’s internal unanimity and organizational coherence.

Can the Chinese government access audio stored by Clubhouse?

The short answer is: probably not, as long as the audio is stored in the U.S.

Clubhouse’s Privacy Policy states that user audio will be “temporarily” recorded for the purpose of trust and safety investigations (e.g. terrorist threats, hate speech, soliciting personal information from minors, etc.). If no trust and safety report is filed, Clubhouse claims that the stored audio is deleted. The policy does not specify the duration of “temporary” storage. Temporary could mean a few minutes or a few years. The Clubhouse privacy policy does not list Agora or any other Chinese entities as data sub-processors.

If Clubhouse stores that audio in the U.S., the Chinese government could ask the U.S. government to make Clubhouse transfer the data under the U.S.-China Mutual Legal Assistance Agreement (MLAA). That request would likely fail, however, due to the MLAA’s provisions allowing the United States to reject requests that would infringe on users’ free speech or human rights — such as requests involving politically sensitive speech on Clubhouse (Tiananmen, Hong Kong, Xinjiang, etc.). (The Chinese government could not demand audio clips directly from Clubhouse, as U.S. federal law prohibits such disclosures.)

The Chinese government could, however, legally demand audio (or other user data) stored in China if the app’s creator, Alpha Exploration Co., has a partner or subsidiary in China with access to the data. Besides Agora, there is no known evidence to suggest that Alpha Exploration Co. has a Chinese partner or stores user data within China.

In sum: assuming the app maker doesn’t have a Chinese partner or store data in China, then the Chinese government probably could not use legal processes to obtain Clubhouse audio data. Depending on just how “temporary” Clubhouse’s storage is, Clubhouse might not have data to hand over through legal processes in any event. However, if the Chinese government could obtain audio directly from Clubhouse’s backend infrastructure on Agora, it might not resort to using international legal channels to seek the data.

Are mainland users likely to face reprisals for speech on Clubhouse?

For the Chinese government to punish Clubhouse users who visited or spoke in sensitive chatrooms, at least two conditions would need to be met.

First, the Chinese government would need to know which users were present in which chatrooms. It could gain this information manually, through reporting from other users present in the room, or from the back-end, via Agora, as discussed above.

For manual data gathering, someone in the room would need to manually record other users’ profiles. Their public profiles sometimes display identifying information, such as photos, phone numbers or WeChat accounts. (Phone numbers and WeChat accounts are real-name registered in China. Photos could be identified through facial recognition algorithms.) However, most Clubhouse profiles do not display identifying information. In that case, the government would need to access identifying information through its own surveillance mechanisms, or via Agora.

Chinese domestic surveillance capabilities are opaque, but assumed to be significant. It is possible that the Chinese government can access mainland users’ data or metadata without recourse to either Clubhouse or Agora, similar to how the U.S. government eavesdropped on web traffic, as revealed by Edward Snowden. As detailed above, the Chinese government could easily intercept plaintext metadata, such as room IDs and user IDs, sent from users’ devices. If the government doesn’t have independent access to user data, it would need to request and receive data from either Agora or Clubhouse. As stated above, it is not clear that the government could easily do so. Agora claims not to store user data, and Clubhouse is highly unlikely to provide it.

Second, the Chinese government must want to punish users of the app. Whether they would is unclear. Research has shown that the Chinese government can sometimes be tolerant of public criticism when that criticism doesn’t gain a wide following and doesn’t promote collective action. On these dimensions, Clubhouse is a grey area. Because the app is invite-only and only available on comparatively-expensive iPhones (less than 10% of all Chinese users), the app was probably not widely used beyond China’s urban elite. In addition, each Clubhouse chat room can host a maximum of five thousand users — a large number, but perhaps not threateningly large. All of these factors might mitigate Clubhouse’s severity from a government perspective.

On the other hand, the Chinese government has proven highly sensitive to apps that coordinate action in the real world, like the short-lived humor app Neihan Duanzi. Clubhouse is thus a unique space: it is a “meet-up” of sorts (which the Chinese government doesn’t like) but it is also semi-private and not yet widely distributed (which might lead to greater government toleration). Ultimately, we can only speculate.

If the government did want to punish domestic users of the app, the public might not know about it — nor might the users themselves. In recent years the Chinese government has fostered the growth of surreptitious censorship mechanisms for black-listed citizens, such as escalating users’ sensitivity indices on WeChat, an all-purpose domestic social media app. Black-listed users might send messages to their friends, only to realize that the message appeared on their screen but not their friends’. The government could also engage in threatening but not outright punishing behavior, such as inviting users to “tea.” Even if that happened, we might never know whether activity on Clubhouse triggered the invitation.

Why did the Chinese government ban the app now?

Why ban the app at all?

For years, the Chinese government has blocked websites or apps that insufficiently conform to its principle of “cyber-sovereignty,” the idea that each country should set the boundaries for cyber-activity within its territory. The Chinese government typically maintains loose definitions for illegal behavior, thus allowing itself maximum flexibility in blocking unwanted content.

The government rarely explains why it blocks individual apps. In the case of Clubhouse, it is likely that the government objected to political conversations concerning Xinjiang, Hong Kong, Tiananmen, censorship, and others. The Global Times, a state-owned nationalistic newspaper which often reflects hardline positions within the government, published an editorial complaining that “political discussions on Clubhouse are often one-sided” and “pro-China voices can be easily suppressed.”

Why ban it now?

Most mainland users of Clubhouse, alongside foreign journalists and analysts, expected the app to be banned eventually. The pressing question was when. While many factors likely contributed to the timing of the app’s ban, here are three possibilities.

First, government censors may not have been at the office. Research by Margaret Roberts, Professor of Political Science at University of California San Diego, has shown that censorship dips on weekends and Chinese holidays. Clubhouse went viral over the weekend, when censors aren’t at the office. This week is also the Lunar New Year celebration, when many employees stop working.

Second, the Chinese government may have wanted to gather information on its citizens. Scholars have long noted the “autocrat’s dilemma” — the challenge authoritarian governments face in gathering accurate measures of public opinion. Because citizens fear reprisal, they lie about their preferences. The Chinese government may actually value spaces like Clubhouse for providing a brief window into (mostly elite) citizens’ authentic political opinions.

Third, banning an app may require time. The Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), which is responsible for banning apps with the Great Firewall, is a large and complex bureaucracy. The decision to ban may have been held up by red tape. The Great Firewall itself, too, is a large and complex technical apparatus. Redirecting its resources may require technical labor.

The answer could also be all of these or none of the above. The preceding is only a preliminary analysis.

Appendix: Technical Analysis

According to Agora’s documentation, audio is relayed through Agora using their real time communication (RTC) standard development kit (SDK). Think of it like an old-time network operator: to reach another person, the operator must connect two users. In this case, Clubhouse app is each user’s telephone, while Agora is the operator.

Clubhouse application’s property list (.plist) file, bundled with the iOS application, contains its Agora application ID

Clubhouse application’s property list (.plist) file, bundled with the iOS application, contains its Agora application ID

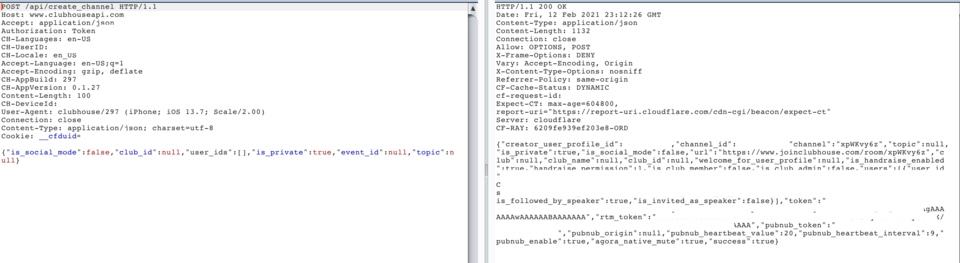

When a user joins or creates a chatroom in Clubhouse, the user’s app makes a request via secure HTTP (HTTPS) to Agora’s infrastructure. (A “request” over HTTP is the most common way of accessing websites; it is likely how you are reading these words right now.) To make the request, the user’s phone contacts Clubhouse’s application programming interface, or “API.” The phone sends the request [POST /api/create_channel] to Clubhouse’s API. The API returns the fields token and rtm_token, where token is the Agora RTC token and rtm_token is the RTM (real time messaging) token. These “tokens” are then used to establish a communication pathway for ensuing audio traffic among users.

SIO then observed a user’s phone send data packets via UDP (a more light-weight transmission mechanism) to a server called `qos-america.agoralab.co`. The user’s packets contain, unencrypted, metadata about the channel, such as whether a user has requested to join a chatroom, the user’s Clubhouse id number, and whether they have muted themselves.

A packet sent to Agora contains, in cleartext, the id of the channel and the user’s ID (see https://docs.agora.io/en/Video/API%20Reference/flutter/rtc_engine/RtcEngine/joinChannel.html)

A packet sent to Agora contains, in cleartext, the id of the channel and the user’s ID (see https://docs.agora.io/en/Video/API%20Reference/flutter/rtc_engine/RtcEngine/joinChannel.html)

After the user has received an RTC token from Clubhouse, their phone then uses the token to authenticate to Agora, so that the chatroom’s encrypted audio can be communicated directly with Agora via a mutually acknowledged pathway. Based on Agora’s documentation, Agora would have access to encryption keys. While the documentation doesn’t specify what kind of encryption is being used, it is likely symmetric encryption over UDP.

The only way that Agora wouldn’t have access to a user’s raw audio is if Clubhouse is employing end-to-end encryption (E2EE) using a customized encryption method. While that is theoretically possible, doing so would require Clubhouse to distribute public keys to all users. That doesn’t exist yet. E2EE is therefore exceedingly unlikely.

Sequence and content of UDP traffic from a device joining a Clubhouse room

Sequence and content of UDP traffic from a device joining a Clubhouse room

The SIO team received this response from Clubhouse and is including it in full. We have not verified any of Clubhouse’s statements:

Clubhouse is deeply committed to data protection and user privacy.

We designed the service to be a place where people around the world can come together to talk, listen and learn from each other. Given China’s track record on data privacy, we made the difficult decision when we launched Clubhouse on the Appstore to make it available in every country around the world, with the exception of China. Some people in China found a workaround to download the app, which meant that—until the app was blocked by China earlier this week—the conversations they were a part of could be transmitted via Chinese servers.

With the help of researchers at the Stanford Internet Observatory, we have identified a few areas where we can further strengthen our data protection. For example, for a small percentage of our traffic, network pings containing the user ID are sent to servers around the globe—which can include servers in China—to determine the fastest route to the client. Over the next 72 hours, we are rolling out changes to add additional encryption and blocks to prevent Clubhouse clients from ever transmitting pings to Chinese servers. We also plan to engage an external data security firm to review and validate these changes.

We welcome collaboration with the security and privacy community as we continue to grow. We also have a bug bounty program that we operate in collaboration with HackerOne, and welcome any security disclosures to be sent directly to security@joinclubhouse.com.